A new study led by Flinders University points to the importance of sleep quality in the aftermath and recovery process in sports-related concussion, a common form of mild traumatic brain injury.

Results from a study published in Nature and Science of Sleep found that sleep appears to ‘improve’ in the 8 weeks after concussion, including longer duration sleep, better sleep efficiency, and even longer deep sleep as the recovery progresses.

“Little is known about sleep after a concussion, despite sleep arguably being the more important process to allow the brain to function optimally,” says Flinders University sleep researcher Dr David Stevens, who treats and researches sports-related concussion.

The results of this small-scale study gives credence to previous studies in animals showing that improving sleep supports recovery from brain injury, and therefore should be explored and monitored in detail for recovery and other effects of concussion such as loss of cognitive function, alertness and depression and anxiety.

“We hypothesise sleep can be a key indicator of the the brain trying to repair/recover from the concussion.”

Previous studies have linked deep sleep leads to neural plasticity, and activation of the glymphatic system that removes amyloid-β and τ-proteins, both of which are implicated in Chronic Traumatic Encephalopathy (CTE), a progressive and fatal brain disease associated with repeated traumatic brain injuries, including concussions and repeated blows to the head.

The new study, based evidence collected from athletes who experienced a sports-related concussion, underwent overnight sleep studies within seven days of the concussion (acute stage) and again eight weeks after the concussion (sub-acute stage).

This study indicates better sleep in participants with a concussion compared to the population norm. Sleep also appeared to further improve in the eight weeks after concussion compared to sleep immediately after concussion.

“We speculate that the improvement in sleep was an attempt by the brain to heal itself,” Dr Stevens says.

“More research in a larger population is needed to explore this hypothesis, and investigate other neurophysiological and neurocognitive measures to examine whether changes in sleep during recovery from concussion results in changes to other aspects of the head trauma.

“I am not only advocating for improved research in a range of areas in concussion, but also for players, clubs and organisations to stop treating concussion likes it’s a scratch or a ‘corky’, but rather a clinical issue that has potential ramifications worse than any dislocation or fracture.”

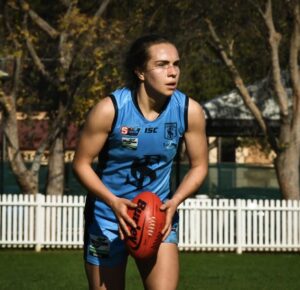

Former SANFLW player Maya Rigter says she is still recovering from three concussions, the last of which forced her to retire on 19 March.

After 57 games with Sturt Football Club and “still loving football”, she decided to retire “due to the significant risk another concussion poses to my professional medical career and future health”.

Currently studying physiotherapy, Ms Rigter says the decision to stop playing “broke my heart” but ongoing symptoms were having a significant impact on her life, “particularly university with cognitive ability slow to return”.

The article – Electroencephalographic Changes in Sleep During Acute and Subacute Phases After Sports-Related Concussion (2023) by David J Stevens, Sarah Appleton, Kelsey Bickley, Louis Holtzhausen and Robert Adams has been published in Nature and Science of Sleep (Dove Press) DOI: 10.2147/NSS.S397900

As well as sleep research at Flinders University, Dr Stevens collaborates with NeuroFlex research to develop objective digital markers of concussion to help guide return-to-play decisions in a range of sports from football to rugby union, rugby leave and cycling.

Acknowledgements: Funding for the study was provided by the Flinders Foundation