Big bones from the extinct ‘thunder bird’ or dromornithid, excavated in the northern reaches of the Flinders Ranges and near Alice Springs, have yielded new insights into their slow breeding patterns.

Studies of the microstructure of these giant Australian fossil bones by University of Cape Town (UCT) and Flinders University vertebrate palaeontologists indicate their size and breeding cycle gradually changed over millennia but ultimately couldn’t keep pace with the environmental changes around them.

“Sadly for these amazing animals, which already faced rising challenges of climate change as the interior of Australia became hotter and dryer, their breeding biology and size couldn’t match the more rapid breeding cycle of modern day (smaller) emus to keep pace with these more demanding environmental conditions,” says Professor Anusuya Chinsamy-Turan, from UCT, South Africa.

“Questions, such as how long these gigantic birds took to reach adult size and sexual maturity, are key to understand their evolutionary success and their ultimate failure to survive alongside humans.

“We studied thin sections of the fossilised bones of these thunder birds under the microscope so that we could identify the biological signals recorded within. The microscopic structure of their bones gives us information about how long they took to reach adult size, when they reached sexual maturity, and we can even tell when the females were ovulating.”

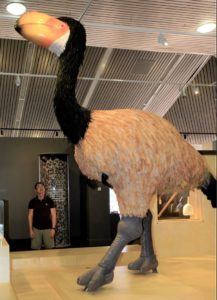

The research, published in The Anatomical Record, compares the bones of the oldest and largest mihirung (the Aboriginal name for the bird), Dromornis stirtoni, which lived 7 million years ago, stood up to 3m tall and had a mass of up to 600kg – through to the smallest of the flightless birds, Genyornis newtoni – the last species of mihirung – which lived alongside early emus, now the world’s third-largest bird.

The study indicates Dromornis stirtoni – arguably the largest bird ever to live on Earth – took a long time to grow to full body size and to become sexually mature, possibly up to 15 years.

By the late Pleistocene era of Genyornis newtoni, the climate was much drier with more seasonal variation and unpredictable droughts. These birds grew six times larger than emus with a body mass around 240kg, but grew to adult size faster than the first mihirung, likely within 1-2 years and started breeding soon thereafter.

However, they needed several more years to reach adult body size and so their growth strategy was still quite slow compared to nearly all modern birds that reach adult size in a year and can breed in the second year of their life.

Co-author Flinders University Associate Professor Trevor Worthy from Flinders Palaeontology, adds that dromornithids were contemporary with emus for a very long time before the final mihirung went extinct.

“In fact, they persisted together through several major environmental and climatic perturbations,” he says. “However, while Genyornis was better adapted than its ancestors, and survived through two million years of the Pleistocene when arid and drought conditions were the norm, it was still a slow-growing and slow-breeding bird compared to the emu.

“The differing breeding strategies displayed by emus and dromornithids gave the emu a key advantage when the paths of these birds crossed with humans about 50 thousand years ago, with the last of the dromornithids goings extinct about 40 thousand years ago.

“In the end, the mihirungs lost the evolutionary race, and an entire order of birds was lost from Australia, and the world.”

Although the bones of the late Pleistocene dromornithids show their reproductive biology had responded to ever-changing climate pressures, and that they were breeding sooner than their ancestors did, the strategy did not approach the reproductive efficiency shown by large ratite birds today.

For example, emu grow to full adult size and breed within 1-2 years. This type of breeding strategy allows their populations to rebound when favourable conditions return after periods of drought or food shortages which could cause population declines.

Osteohistology of Dromornis stirtoni (Aves: Dromornithidae) and the biological implications of the bone histology of the Australian mihirung birds (2022) by A Chinsamy, WD Handley and TH Worthy has been published in The Anatomical Record (Wiley), 1–22. https://doi.org/10.1002/ar.25047.

Read more in The Conversation: Putting the bones of giant, extinct ‘thunderbirds’ under the microscope reveals how they grew