Serving up too much soft food to animals rescued into captivity might reduce their survival chances when released back into the wild.

An international team of researchers, led by Dr Rex Mitchell at Flinders University, have shed light on the potentially harmful effects soft food diets can have on the skull of growing animals.

Each year, thousands of young animals across the world are rescued and rehabilitated by wildlife carers. The aim is to give these animals time to heal and grow until they are fit enough and old enough to be released.

“Some scientists have suggested that captive diets may have unintended, negative effects on skull development that could impact the successful reintroduction of animals into the wild,” says Dr Mitchell.

“We wanted to know how much growing up on a diet that doesn’t need much biting can impact the ability of an animal to bite effectively in adulthood.”

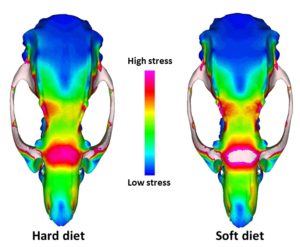

Fortunately, Dr Mitchell and colleagues had a large collection of computed-tomography (CT) scans collected back in 2012 of rats that were fed different diets, from when they finished suckling all the way to adulthood. Using these scans, Rex created three-dimensional digital models of each rat skull and carried out computer-based 3D bite simulations to see which skulls were the weakest.

Every time a bone is used to perform an action, it bends a little bit. The more often a bone bends over time, the thicker the bone can get – especially when moving or lifting heavier things. So the researchers expected less work for food would cause thinner bones to grow in the skull.

“The simulations showed that the rats fed the softest diet indeed grew up to have the weakest skulls, but our research also found something unexpected,” says Professor Stephen Wroe, co-author from the University of New England in Armidale, Australia.

In some parts of the skull it wasn’t the rats fed the softest diet that were the weakest, but instead the group that was switched from hard to soft food as juveniles.

“This certainly surprised us. So we had to do some digging in the literature to explain it,” Rex says.

Interestingly, earlier studies show that when rats in space experience sudden and prolonged disuse of bone, the number of cells responsible for depositing more layers decreases.

“We often think of bones as simple hard objects,” says Dr Rachel Menegaz, co-author of the study from the University of North Texas Health Science Center where the study was carried out.

“But bone is actually a complex living tissue that is constantly adapting.”

These results suggest that if an animal suddenly stops needing to bite its food during development, it might then lose many of the cells needed for depositing bone while it is still growing, impacting on normal bone growth and resulting in a weaker adult skull.

So what does all this mean for the rehabilitation and releasing of our furry friends? Well, just like for sports and exercise, it’s about conditioning the body to be able to better perform the tasks that are expected.

If rescued animals are fed diets that are overly reliant on softer, processed, pre-peeled, cut, or portioned foods, their skulls and jaw muscles won’t be as prepared for the more difficult foods they may need to eat in the wild. The findings are published in Integrative Organismal Biology.