The sighting of a seven-metre shark off the South Australia coast has excited the world’s media with some making reference to the great white that featured in the classic 1975 film Jaws.

The sighting of a seven-metre shark off the South Australia coast has excited the world’s media with some making reference to the great white that featured in the classic 1975 film Jaws.

It was certainly a big shark but there are tales of even bigger sharks lurking in our waters. A quick Google search on “megalodon” brings up around 1.2 million hits about this monster prehistoric shark, made famous in the 2002 eponymous B-movie, says John Long, the Strategic Professor in Palaeontology at Flinders University.

Professor John Long’s extended article, as outlined here, was the top trending article in The Conversation last week. Read the full version at the link above.

Web pages feature frightening movie clips claiming to show evidence that this gigantic fossil shark, once reaching around 17m in length, is still alive out there, perhaps living in deep seas where they escape detection.

Megalodon (meaning “big tooth”) is really the vernacular name used for Carcharocles megalodon, an extinct relative of today’s white and mako sharks in the family Lamnidae.

Megalodon is known from its huge fossil teeth, the largest being 18 centimetres long, found nearly all around the globe in fossil marine deposits. It lived from about 16 million to 2.6 million years ago.

Around 400 years ago, megalodon teeth were thought to be petrified tongues. In 1667, the Danish anatomist Nicolas Steno figured out from his dissection of a white shark head that they were the teeth of ancient large sharks.

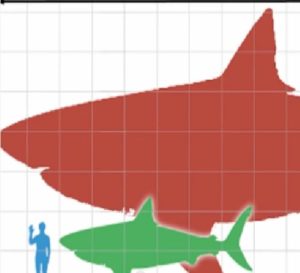

Scaling up teeth and jaw size with known living sharks yields an approximate maximum size for megalodon around 17m. But, in weight, it would have been at least ten times the mass of a large white shark.

Unlike whites, we deduce that megalodon targeted large baleen whales as its prime prey, as we have found its tooth marks on fossil whale bones and sometimes teeth stuck into whale fossils. Some of these specimens can also be put down to scavenging behaviour.

In recent years several scientific papers by Dr Catalina Pimiento, of the Florida Museum of Natural History, have greatly elucidated our knowledge about this impressive prehistoric predator. Her study calculating its trends in body size through time show its average size was likely around 10m for most of its 14-million year reign.

We know that its raised its young (starting at 2m in length) in nursery areas of the eastern Pacific. Another study confirms that the species died out at least 2.6 million years ago, based on many reliably dated fossil sites.

Dr Pimiento suggests that the the modern baleen whale fauna was probably established after the extinction of megalodons.

The reasons for megalodons demise are unknown, but could relate to either climate change or biological factors, like the events concerning the evolution and migration of whales to colder Antarctic waters where the sharks could not go.

I proposed this idea back in 1995 in the first edition of my book The Rise of Fishes.

Dr Pimiento’s new research currently in press seems to support the view. She told me: “I found no evidence for a relationship between megalodon distribution and climate, and therefore, no support for such hypotheses. Instead, I found that megalodon trends in distribution coincide with diversification events in marine mammals and in other sharks, further supporting the biotic set of hypotheses.”

It seems likely that the growth and huge size of modern baleen whales, the largest animals on the planet, could well have been driven by predation pressures from megalodons.

Their ability to endure and feed in near freezing Antarctic waters might have been a key reason why megalodons went extinct. Thankfully, for all of us who love swimming and diving in the sea.