Algorithms can predict what movies or songs you might like, but they can also predict which species a predator would most likely eat.

Researchers at Flinders University’s Global Ecology Laboratory have been using machine learning to identify species interactions and can predict which species are most likely to go extinct, so that intervention can be planned before this happens.

“The planet is facing an environmental crisis, with climate change, invasive species, habitat loss, and other human-related activities causing a multitude of extinctions,” says Dr John Llewelyn, Research Fellow at Flinders University’s College of Science and Engineering.

“Many of these extinctions are mediated by species interactions, triggered by the loss or gain of interactions with other species, and we have found that machine learning can predict who eats whom in a world of connected species.”

Dr Llewelyn says ‘co-extinctions’ are extinctions caused by declines or extinctions in other, interacting species, such as a predator going extinct following the loss of its prey.

Conversely, invasive predators such as cats, foxes and brown tree snakes can cause extinctions in naïve native prey that have not dealt with similar predators in the past.

“These are extinctions resulting from vulnerable species gaining interactions with new predators, so knowing which species interact is essential for predicting and avoiding future extinctions,” adds Dr Llewelyn. “However, at present we only know a tiny fraction of the species interactions that occur — or that could occur, in the case of invasive species — and this makes predicting extinctions difficult.”

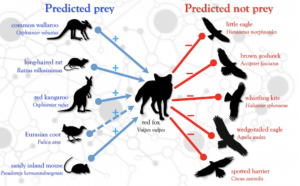

The Flinders team’s new research found that machine learning techniques can use a species’ traits to predict predator-prey interactions accurately for birds and mammals. By identifying species that interact, machine learning can then help to predict and hopefully avoid extinctions before they happen.

The Flinders team’s new research found that machine learning techniques can use a species’ traits to predict predator-prey interactions accurately for birds and mammals. By identifying species that interact, machine learning can then help to predict and hopefully avoid extinctions before they happen.

The algorithm learns how traits are related to species interactions from information on which species interact, which species don’t interact, and the traits of the species involved. This type of AI can then be provided with a list of species and traits to predict which of the species in the new list interact.

“We can use this method to fill in the many gaps we have in our knowledge of species interactions,” says Dr Llewelyn.

These gaps include undocumented interactions that are happening today, interactions between ancient, long-extinct species, and interactions invasive species would have if they were introduced to a new area.

“By knowing which species interact, we can identify how environmental disturbances — such as climate change and introduced species — can have cascading effects in ecological communities, allowing us to understand how extinctions happen.”

Species interactions play a fundamental role in ecosystems, although few ecological communities have complete data describing such interactions, which is an obstacle to predict how ecosystems function and respond to perturbations.

“Humans depend utterly on biodiversity and healthy ecosystems, so we have a responsibility to maintain biodiversity for its own sake as well as for the benefits it provides human societies,” says Dr Llewelyn.

The research – “Predicting predator-prey interactions in terrestrial endotherms using random forest”, by John Llewelyn, Giovanni Strona, Christopher Dickman, Aaron Greenville, Glenda Wardle, Michael Lee, Seamus Doherty, Farzin Shabani, Frédérik Saltré and Corey Bradshaw – has been published in the journal Ecography. http://doi.org/10.1111/ecog.06619