The discovery of an early wombat relative with a powerful bite and a possum with bizarre nut-cracker teeth helps fill in a lost part of a 25 million-year-old fossil site puzzle in central Australia’s Red Centre.

The latest Flinders University palaeontology research of fossil remains from the Northern Territory give key insights into the diet and lifestyle of long extinct marsupials which lived in a once-lush forests landscape dominated by megafauna including giant flightless birds and crocodiles.

“These curious beasts are members of marsupial lineages that went extinct long ago, leaving no modern descendants,” says PhD candidate Arthur Crichton, from the Flinders University Palaeontology Laboratory.

“Learning about these animals helps put the wombat and possum groups that survive today in a broader evolutionary context.”

The fossil remains, deposited about 25 million years ago in the late Oligocene, were found by Flinders University palaeontologists in 2014, 2020 and 2022 near the small Arrernte township of Pwerte Marnte Marnte in the southern Northern Territory.

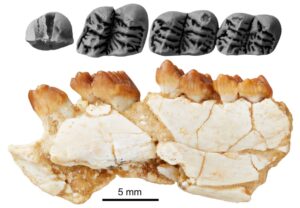

“The newly described species, an early possum named Chunia pledgei, has teeth that are a dentist’s nightmare, with lots of bladed cusps that are positioned side by side, like lines on a barcode.

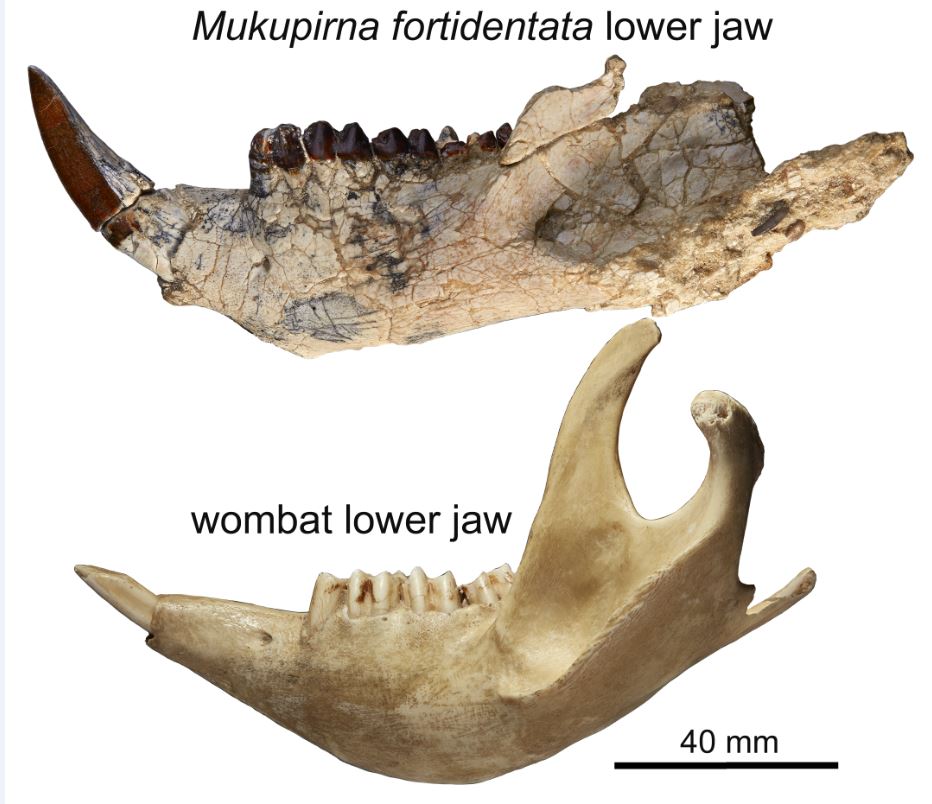

“The other new species, called Mukupirna fortidentata, is a larger distant relative of wombats and has jaws and teeth shaped to suggest it had a pretty powerful bite.

“Its incisors are more like those of tree-squirrels than wombats, being strikingly large and steeply upturned. It would have been pretty good at processing hard foods like touch fruits, seeds and bulbs.

“Intriguingly, the molars are actually pretty similar to those of some monkeys such as macaques. Modern wombats, by comparison, have teeth that grow continuously throughout their life to counteract the highly abrasive nature of their main food, grass,” adds co-author Professor Gavin Prideaux, director of the Flinders University Palaeontology Lab.

Weighing about 50kg, Mukupirna fortidentata was among the largest marsupials of its time.

This species is thought to be part of an extinct evolutionary lineage, Mukupirnidae, that diverged from a common ancestor with wombats (Vombatidae) more than 25 million years ago.

“While wombats were very successful over the succeeding period, the mukupirnids seem to have gone extinct sometime before the end of the late Oligocene (25-23 million years ago),” Professor Prideaux says.

“This is an interval in Australia’s climate that saw a steady increase in aridity and seasonally restricted rainfall, reshaping the environment.”

Evidence of the ancient wombat was compiled from 35 specimens from different individuals, including a partial skull and several lower jaws.

Meanwhile the molar morphology of the early possum Chunia pledgei is characteristic of species in the poorly known extinct family, Ektopodontidae.

The new species is named after South Australian palaeontologist Neville Pledge, who discovered fossils of younger members of the ektopodontid group in rocks east of Lake Eyre.

“All ektopodontids have very strange teeth, with lots of bladed cusps positioned side by side like lines on a barcode and, like barcodes, each species has teeth that are subtly different in shape,” says Mr Crichton.

“Unlike other ektopodontids, fossils from the new species reveal that it had pyramid-shaped rather than bladed cusps near the front of its mouth. This adaptation might have been useful for puncture-crushing hard food items – a bit like a nut-cracker.

“Unfortunately, ektopodontids are tantalisingly rare in the fossil record, known only from isolated teeth and several partial jaws.

“We know that these animals had a lemur-like short face, with particularly large forward-facing eyes, but until more complete skeletal material is known, their ecology will likely remain mysterious.”

A modern day brush-tailed possum and southern hairy-nosed wombat

A new species of Mukupirna (Diprotodontia, Mukupirnidae) from the Oligocene of Central Australia sheds light on basal vombatoid interrelationships (2023) by Arthur I Crichton, Trevor H Worthy, Aaron B Camens, Adam M Yates, Aidan MC Couzens and Gavin J Prideaux has been published in Alcheringa: An Australasian Journal of Palaeontology (Taylor & Francis online) DOI: 10.1080/03115518.2023.2181397.

The second article, A new ektopodontid possum (Diprotodontia, Ektopodontidae) from the Oligocene of central Australia, and its implications for phalangeroid interrelationships (2023) by Arthur I Crichton, Trevor H Worthy, Aaron B Camens and Gavin J Prideaux was published in the Journal of Vertebrate Palaeontology DOI: 10.1080/02724634.2023.2171299.

Read more in The Conversation: 25 million-year-old fossils of a bizarre possum and strange wombat relative reveal Australia’s hidden past