The largest flightless bird ever to live weighed in up to 600kg and had a whopping head about half a metre long – but its brain was squeezed for space.

Dromornis stirtoni, the largest of the ‘mihirungs’ (an Aboriginal word for ‘giant bird’), stood up to 3m and had a cranium wider and higher than it was long due to a powerful big beak, leading Australian palaeontologists to look inside its brain space to see how it worked.

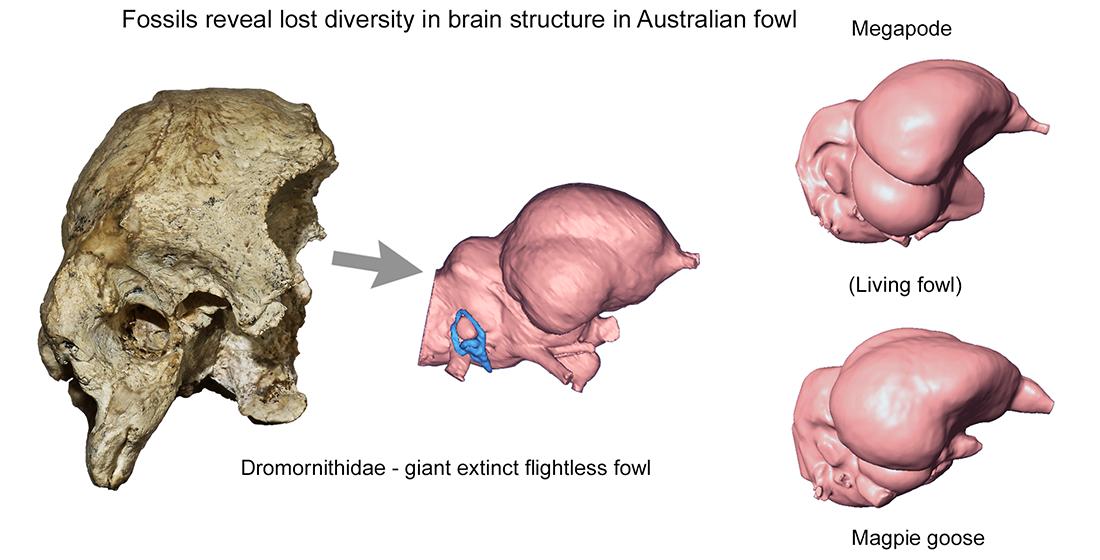

The new study, just published in the journal Diversity, examined the brains of the extinct giant mihirungs or dromornithid birds that were a distinctive part of the Australian fauna for many millions of years, before going extinct around 50,000 years ago.

“Together with their large, forward-facing eyes and very large bills, the shape of their brains and nerves suggested these birds likely had well-developed stereoscopic vision, or depth perception, and fed on a diet of soft leaves and fruit,” says lead author Flinders University researcher Dr Warren Handley.

“The shape of their brains and nerves have told us a lot about their sensory capabilities, and something about their possible lifestyle which enabled these remarkable birds to live in the forests around river channels and lakes across Australia for an extremely long time.

“It’s exciting when we can apply modern imaging methods to reveal features of dromornithid morphology that were previously completely unknown,” Dr Handley says.

The new research, based on fossil remains ranging from about 24 million years ago to the last in the line (Dromornis stirtoni), indicates mihirung brains and nerves are most like those of modern day chickens and Australian mallee fowl.

“The unlikely truth is these birds were related to fowl – chickens and ducks – but their closest cousin and much of their biology still remains a mystery,” says vertebrate palaeontologist and senior author Associate Professor Trevor Worthy. “While the brains of dromornithids were very different to any bird living today, it also appears they shared a similar reliance on good vision for survival with living ratities such as ostrich and emu.”

The researchers compared the brain structures of four mihirungs – from the earliest Dromornis murrayi at about 24 million years ago (Ma) to Dromornis planei and Ilbandornis woodburnei from 12 Ma and Dromornis stirtoni, at 7 Ma.

Ranging from cassowary in size to what’s known as the world’s largest bird, Flinders vertebrate palaeontologist Associate Professor Worthy says the largest and last species Dromornis stirtoni was an “extreme evolutionary experiment”.

“This bird had the largest skull but behind the massive bill was a weird cranium. To accommodate the muscles to wield this massive bill, the cranium had become taller and wider than it was long, and so the brain within was squeezed and flattened to fit.

“It would appear these giant birds were probably what evolution produced when it gave chickens free reign in Australian environmental conditions and so they became very different to their relatives the megapodes – or chicken-like landfowls which still exist in the Australasian region,” Associate Professor Worthy says.

The large, flightless birds Dromornithidae – also called demon ducks of doom or thunder birds – existed from the Oligocene to Pleistocene Epochs.

During prehistory, the body sizes of eight species of dromornithids became larger and smaller depending climate and available feed.

The Flinders researchers used the skulls of fossil birds to extract endocasts of the brains to describe how these related to modern birds such as megapodes and waterfowl. Brain models were also made from CT scans of five other dromornithid skulls from fossil sites in Queensland and the Northern Territory. The oldest 25 Ma Dromornis murrayi specimen was found in the famed Riversleigh World Heritage Area in Queensland.

The Flinders researchers used the skulls of fossil birds to extract endocasts of the brains to describe how these related to modern birds such as megapodes and waterfowl. Brain models were also made from CT scans of five other dromornithid skulls from fossil sites in Queensland and the Northern Territory. The oldest 25 Ma Dromornis murrayi specimen was found in the famed Riversleigh World Heritage Area in Queensland.

The paper, ‘Endocranial Anatomy of the Giant Extinct Australian Mihirung Birds (Aves, Dromornithidae)’ by WD Handley and TH Worthy has been published in Diversity, 13(3), 124; DOI: 10.3390/d13030124

This work was supported by the Australian Research Council DE130101133, and DP180101913, and an Australian Government Research Training Program Scholarship.