A new study adds another layer to the remarkable evolutionary transition of life from water to land on Earth.

The international study of the prehistoric ‘relic’ tetrapods (the first terrestrial vertebrates), including salamander and lobe-finned lungfish and coelacanths, adds another perspective to the evolution of other four-legged land animals, including related animals such as frogs and reptiles which live in both terrestrial and aqueous environments.

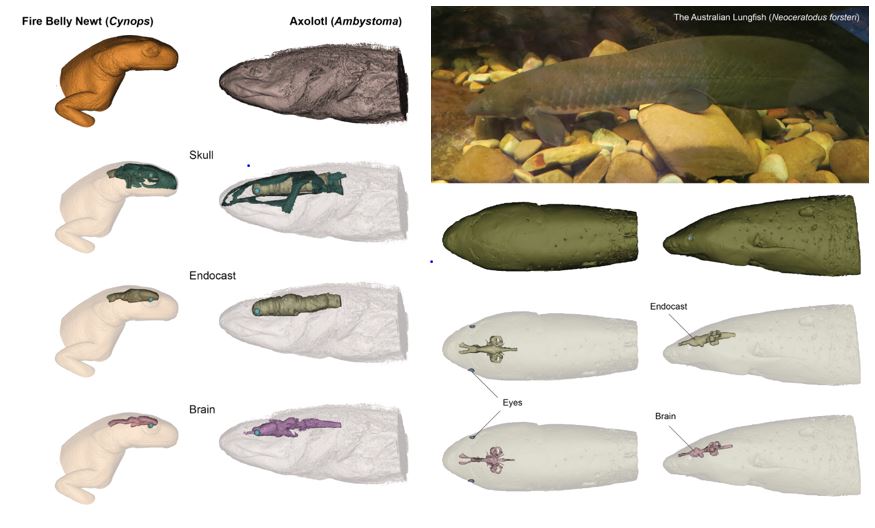

Using micro-CT and MRI scans to make 3D models of small animal heads, palaeontology researchers from the University of Edinburgh, University of Calgary and Flinders University shone a light on how the eating habits and brains of the some of the first land-based lifeforms prepared them for life on dry land.

In a study published in the journal Royal Society Open Science, Flinders University researcher Dr Alice Clement says the transition from water to land by the earliest tetrapods (backboned animals with four legs rather than fins) in the Devonian Period (359-419 million years ago) is seen as one of the greatest steps in evolution. But she says little is known about the changes in brain morphology over this transition.

“Coelacanth and lungfish are the only lobe-finned fish alive today, but their relatives were the lineage of fish that first left the water to colonise land,” Dr Clement says.

“Soft tissue, such as brains and muscles, doesn’t survive in fossil records so we studied the brains of living animals, and the internal space of the skull or ‘endocast’ to figure out what brains of fossils animals must have looked like.

“Our main finding is that salamanders and lungfish have brains quite similar in size and shape to each other, while the coelacanth is a real outlier with a tiny brain.”

University of Edinburgh researcher Dr Tom Challands says the high-tech scanning of braincase and jaw structure in six sarcopterygians shows a correlation between how tight or loose the brain fills the skull.

“For the first time, we have been able to demonstrate the interplay between how the jaw muscles affect how the brain sits inside the brain cavity,” says first author Dr Tom Challands, from University of Edinburgh’s Grant Institute of Earth Sciences.

“As animals made their way out of water and on to land, their food sources changed and the brain had to adapt to a completely new way of living – different sensory processing, different control for movement, balance, and so on,” he says.

“Each of these plays against each other and our work basically shows the effect of masticatory (eating) changes are balanced with maintaining a skull that can support and protect the brain.”

He says some of the features of these earliest land animals is reflected in other modern animals.

“Moreover we see similarities between the fish and land animals, suggesting that some muscle-brain-skull arrangements were already primed for living on land.”

The paper, Mandibular musculature constrains brain-endocast disparity between sarcopterygians (2020) by TJ Challands, JD Pardo (University of Calgary) and AM Clement has been published in the Royal Society Open Science website DOI: 10.1098/rsos.200933

Background: Sarcopterygians fish comprise about half of all vertebrate diversity today but the vast majority of these are tetrapods (four-limbed vertebrates and their descendants).

There are just eight extant species of sarcopterygian fish: two congeneric species of coelacanth (Latimeria spp.) and three lungfish genera (Neoceratodus, Lepidosiren, Protopterus). Protopterus contains four species and together with Lepidosiren constitute the lepidosirenid lungfishes, which are thought to have diverged from the Neoceratodontid lineage 277 million years ago.

During the Devonian Period sarcopterygian fish were far more diverse and abundant with several now extinct groups.