Destruction of important heritage sites in mining areas of Australia could happen again, Flinders University experts warn.

They say ‘routine destruction’ of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander cultural heritage sites will continue unless various State protection laws or regulations adapt to better balance First Nations peoples’ interests with the day-to-day operations of mining and other industry in regions such as Western Australia’s Pilbara.

The comments follow an unreserved apology lodged by mining company Rio Tinto to the Puutu Kunti Kurrama and Pinikura people after significant 46,000-year-old Aboriginal rockshelters were destroyed during mining operations in the ancient Juukan Gorge area of the Pilbara.

Flinders University Indigenous Australian Archaeology and Anthropology experts – including Professor Claire Smith, Dr Daryl Wesley, Dr Alice Gorman and Professor Amanda Kearney – say the ongoing risk to important cultural sites from mining in the Pilbara could be addressed by changes in Western Australia’s heritage legislation framework.

Legislative change in WA should not just involve delisting sites but give more certainty to industry, while conserving important heritage sites which require further research and investigation, Professor Smith says.

“There certainly is a need for a revision of the processes for permitting Indigenous archaeological sites to be destroyed by development in WA,” say top end archaeologists Professor Smith and Dr Wesley.

“The Aboriginal group signed off on the Section 18 in 2013 after extensive excavations (about 70% of the sites) but the 46,000 BP date came only recently,” Professor Smith points out.

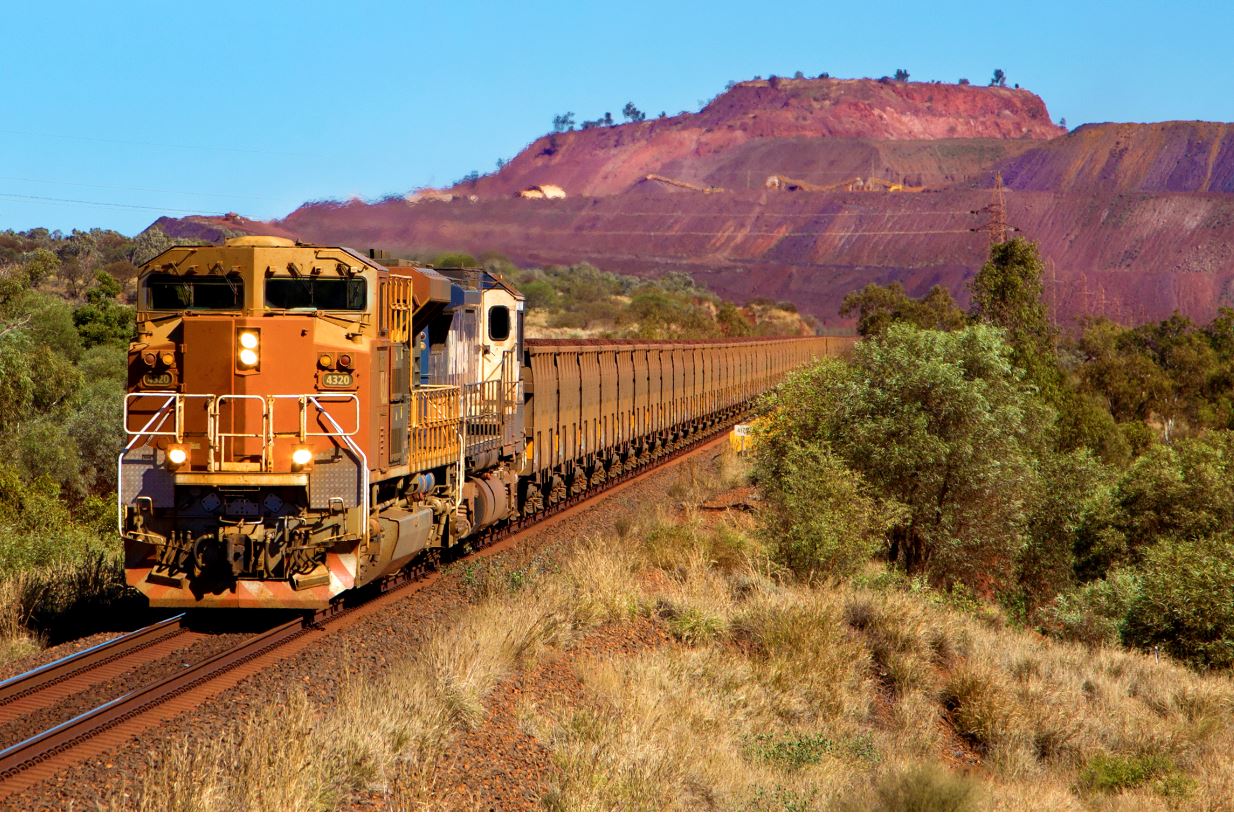

“Archaeological rockshelters have been routinely destroyed over decades in the iron ore mining process in the Pilbara. This is because of the geological context as the mesa and hills predominately consist of iron ore so are mined and destroyed in the open cut mining process,” says Dr Wesley, who studies rockshelters and cultural sites in the Northern Territory.

“Owing to this geological context, a higher proportion of Indigenous archaeological rockshelter sites tend to be destroyed in the Pilbara than elsewhere in Australia. I don’t think this has been properly quantified.”

However Dr Gorman warns that any changes in legislation need to be handled with great care.

“Legislation change is often proposed on the basis of giving Traditional Owners more power and say over what happens,” says Dr Gorman, president of the Anthropological Society of South Australia.

“But changes in regulations and administration can be more effective,” she says.

“If not well resourced to manage their heritage, sweeping changes may leave Traditional Owners as vulnerable to powerful mining companies as they were before – if not more so.”

The latest case in the Pilbara is part of a “long chain in destructive habits that are linked to coloniality,” according to Matthew Flinders Fellow Professor Amanda Kearney.

“Many Australians and politicians might like to ask themselves, how is it, that lack of consultation and repeated injury to Aboriginal people and their lands can become commonplace?” she asks.

“We need political will and legal safeguards to mitigate against this kind of ongoing failure to care for places of Aboriginal ancestral importance.

“So too geographical isolation can no longer be a reason for damaging Aboriginal heritage. In which case, there must be surveillance and care-taking measures built into the design of remote area industries and development action,” Professor Kearney says.

Last month the World Archaeological Congress issued a full statement condemning the destruction of the Juukan Gorge Indigenous site.