Flinders researchers studying the giant cassowary’s eating, breathing and vocal structures have found a new way to gain details about evolution.

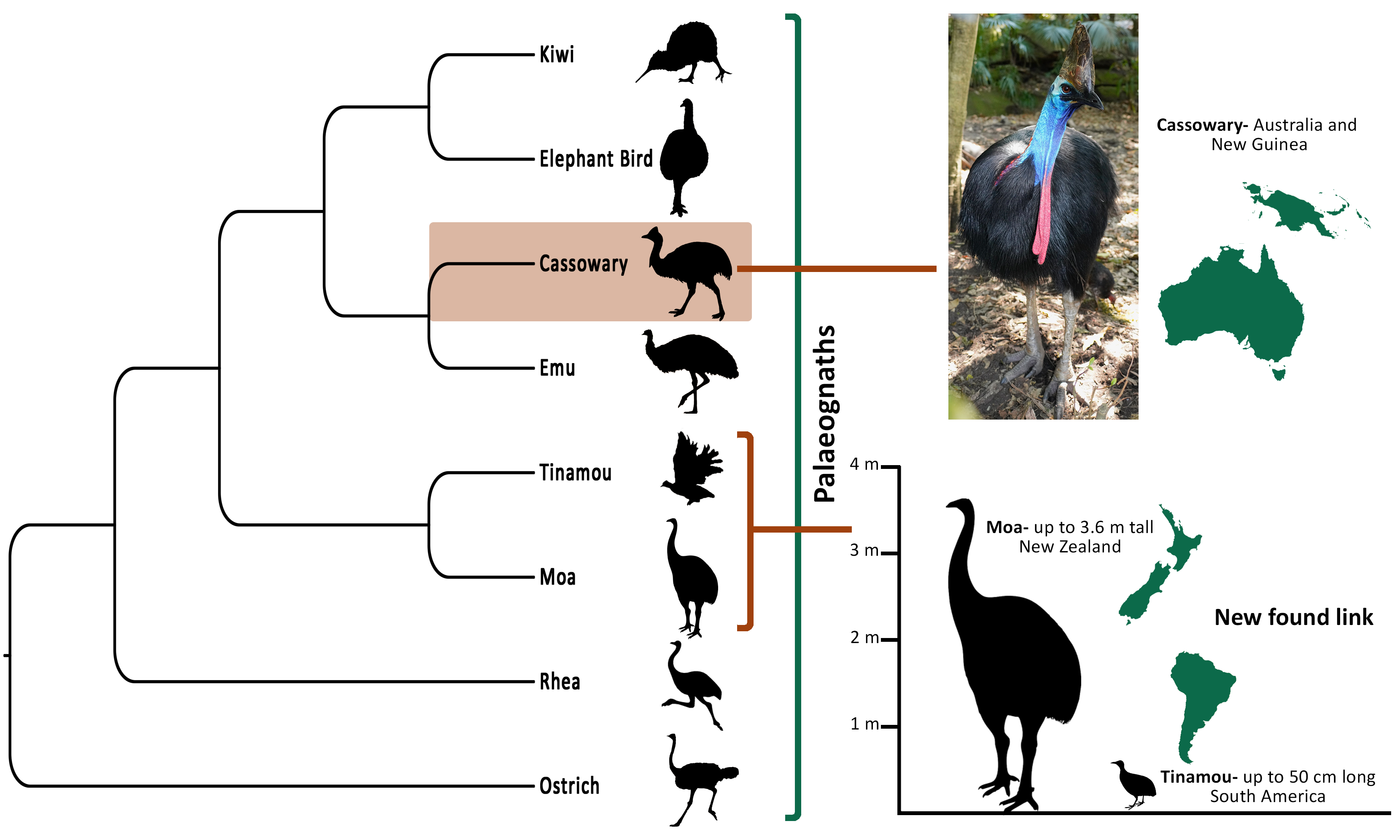

The study even found a surprising missing link between two vastly different birds in the primitive palaeognath family thought to be each other’s closest relative – the small flighted South American tinamou and the extinct New Zealand moa.

The colourful Australian cassowary, the second largest living bird, has been studied for hundreds of years. However, their solitary nature in the dense rainforests of northern Queensland has ensured that many fundamental aspects of these animals continue to elude scientists.

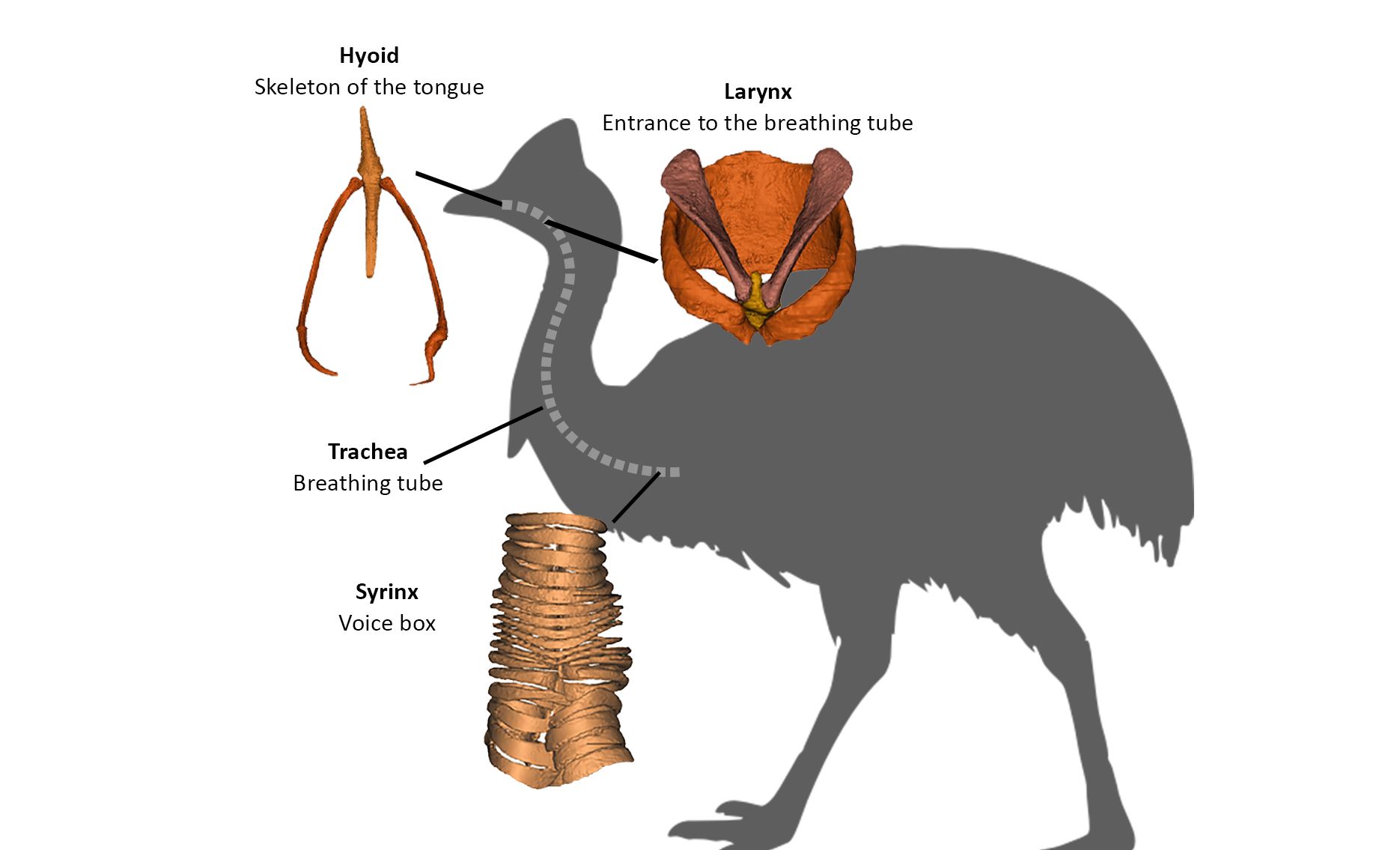

Researchers from Flinders University recognised that the throat structures involved with breathing, eating and vocalising (the syrinx, hyoid, and larynx) were almost totally unknown.

Using advanced scanning technologies, the team was able to 3D image these structures, looking in detail at the anatomy and comparing them to that of other closely related birds.

The results have been published in the international journal BMC Evolutionary Biology.

“Scanning lets us see details that we wouldn’t be able to otherwise, including the shapes of internal structures, without causing damage to them,” says lead author on the paper, PhD student Phoebe McInerney.

The cassowary’s closest relative is the Australian emu, so it was no surprise that they showed many similarities in the throat region.

“What did surprise us though was that despite extensive variation in this region between cassowaries and other primitive living birds, known as palaeognaths, the extinct New Zealand moa and the living South American tinamou were very similar,” she says.

Recent analysis of DNA has concluded that moa and tinamou are closest relatives. However, these results have been met with scepticism by some biologists: the moa was huge and flightless, and the tinamou is a small, flighted partridge-like bird.

And so, for many years, morphological similarities between the moa and tinamou eluded scientists, and yet, hidden deep within the throat, in a structure historically ignored, the answers have been uncovered.

“The morphology of the often-neglected larynx has shown to be far superior than the other anatomical traits biologists previously used to infer evolutionary relationships,” says Associate Professor Trevor Worthy, a co-author on the study.

“The unexpected family tree for primitive birds based on genomic evidence is looking more and more convincing,” says another co-author Professor Michael Lee.

The researchers conclude that despite being historically overlooked, it is important not to forget the small things when studying evolutionary relationships among birds.

The open access article, ‘The phylogenetic significance of the morphology of the syrinx, hyoid and larynx, of the Southern Cassowary, Casuarius casuarius (Aves, Palaeognathae)’ December 2019, by PL McInerney, MSY Lee, AM Clement and TH Worthy, has been published in BMC Evolutionary Biology (Springer Nature) Vol 19, Article 233 DOI: 10.1186/s12862-019-1544-7

The cassowary is most closely related to the emu, followed by the elephant bird, kiwi, moa and then tinamou. All groups of palaeognaths evolved flightlessness and large body size independently from flighted ancestors which flew around the Southern Hemisphere to other countries.

During evolution flighted ancestors of both moa and tinamou would have flown to New Zealand and South America, leading to their diversification into two distinct birds.

The authors acknowledge the support of Adelaide Microscopy and Dr Jones and Partners, and experts and analysis from the Museum of New Zealand Te Papa Tongarewa (Wellington, New Zealand) and Museo de Historia Natural de La Pampa (Santa Rosa, Argentina) for comparisons with other palaeognaths.