New fossils of an ancient legged snake, called Najash, shed light on the origin of the slithering reptiles.

The fossil discoveries, revealed in Science Advances , provide details about how the flexible skull of snakes evolved from their lizard ancestors – and analyses of the family tree have also revealed they possessed hind legs during the first 70 million years of their evolution.

The evolution of the snake body has captivated researchers for a long time – representing one of the most dramatic examples of the vertebrate body’s ability to adapt – but a limited fossil record has obscured our understanding of their early evolution until now.

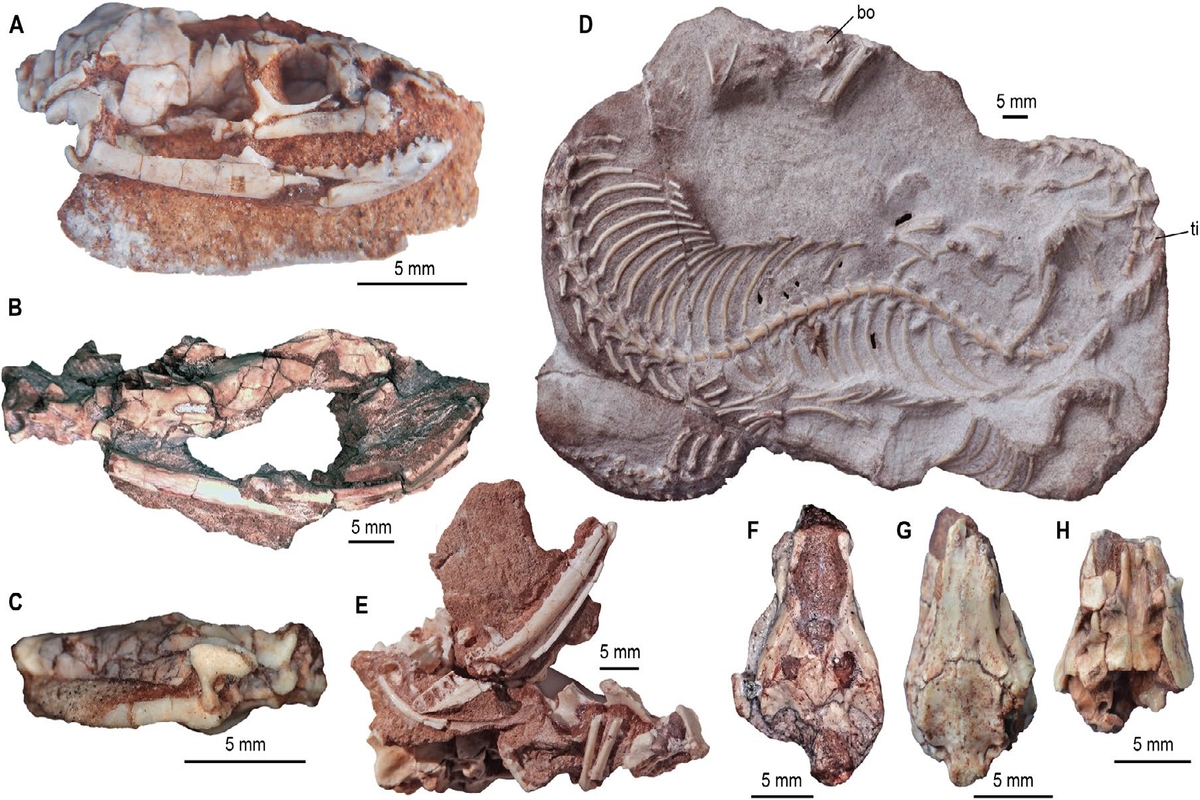

Dr Alessandro Palci, from the College of Science and Engineering at Flinders University, was part of the international research team that performed high-resolution (CT) scanning and light microscopy of the preserved skulls of Najash to reveal substantial new anatomical data on the early evolution of snakes.

“Snakes are famously legless, but then so are many lizards. What truly sets snakes apart is their highly mobile skull, which allows them to swallow large prey items. For a long time we have been lacking detailed information about the transition from the relatively rigid skull of a lizard to the super flexible skull of snakes”.

“Najash has the most complete, three-dimensionally preserved skull of any ancient snake, and this is providing an amazing amount of new information on how the head of snakes evolved. It has some, but not all of the flexible joints found in the skull of modern snakes. Its middle ear is intermediate between that of lizards and living snakes, and unlike all living snakes it retains a well-developed cheekbone, which again is reminiscent of that of lizards.”

Flinders University and South Australian Museum researcher Professor Mike Lee, was also part of the study.

“Najash shows how snakes evolved from lizards in incremental evolutionary steps, just like Darwin predicted.”

The new snake family tree also reveals that snakes possessed small but perfectly formed hind legs for the first 70 million years of their evolution.

“These primitive snakes with little legs weren’t just a transient evolutionary stage on the way to something better. Rather, they had a highly successful body plan that persisted across many millions of years, and diversified into a range of terrestrial, burowing and aquatic niches,” says Professor Lee.

More information is available on The Conversation.

The study was led by Fernando F. Garberoglio at Universidad Maimónides in Buenos Aires, with collaborators M.W. Caldwell at University of Alberta, Dr Alessandro Palci and Professor Mike Lee at Flinders University and the South Australian Museum in Adelaide, R.O. Gómez at Universidad de Buenos Aires, R.L. Nydam at Midwestern University AZ; H.C.E. Larsson at McGill University and T.R. Simões at Harvard University.