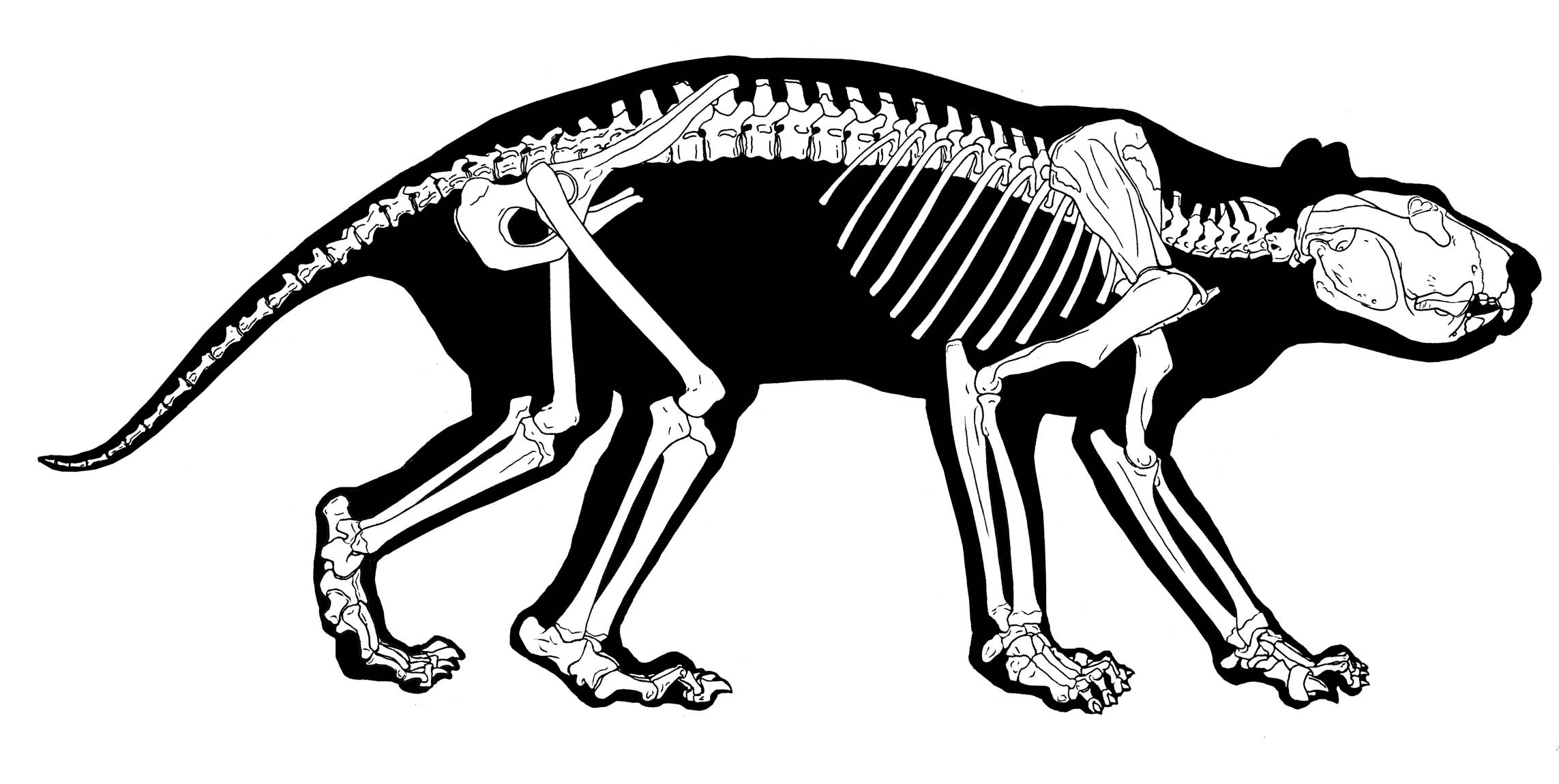

New research into the first complete skeleton of Australia’s legendary ‘Marsupial Lion’ provides extraordinary insights into the species’ hunting ability, social traits – and similarities with the Tasmanian Devil.

As published today in the journal PLOS ONE, the team of researchers from Flinders University set out to analyse the first complete skeleton of the lion (Thylacoleo carnifex) after new remains were discovered, including the only known complete skeleton, in caves in Naracoorte and the Nullarbor Plain.

Their research confirms the animal was a skilled climber, whether it be moving through the canopy or through caves, despite weighing over 100 kilograms.

It had a heavy, muscular tail that would have helped it balance and free up the forelimbs for prey capture and food manipulation.

Interestingly, they reveal the anatomy of the lion is most similar to the Tasmanian Devil, which is the largest marsupial carnivore still living in Australia today.

“These recent fossil discoveries in South Australian caves enabled us to finally assemble a complete skeleton of the marsupial lion, including the tail and collar bone, for the first time ever,” says study author Professor Rod Wells, from the College of Science and Engineering.

“We concluded that the marsupial lion was a stealth or ambush predator of larger prey, a niche not dissimilar to that of the Tasmanian Devil which feeds on smaller prey in comparison,” he says.

The extinction of Australia’s largest marsupial predator has intrigued palaeontologists who have tried to determine the lion’s lifestyle since it was first described using incomplete skull and jaw fragments in 1859.

Recent fossil discoveries included the first known remains of the tail and collarbone, and the authors compared its anatomy to living marsupials, revealing the similar biology and behaviour of the ‘lion’ when compared to the Tasmanian Devil (Sarcophilus harrisii).

“Our analysis of the tail suggests that it was held up in the air and that it was being used in a way that differs from all living marsupials,” says Dr Aaron Camens, Lecturer of Paleontology at Flinders University.

The researchers haven’t determined whether the lion was a cooperative hunter or simply an opportunist, however the fact multiple adults and young were found in caves suggest they operated in social groups.

“Examining the whole skeleton reveals what a truly unique animal Thylacoleo was. It looked like a cross between a possum and a wombat, climbed a bit like a koala, and moved with the stiff-backed gait of a Tasmanian Devil, all whilst filling a niche different to any other animal on earth.”

For millions of years, Thylacoleo carnifex was Australia’s largest and most ferocious mammalian predator, using its climbing ability to ambush prey until the megafauna disappeared around 40,000 years ago.

“It has taken 160 years since discovery of skull and jaw fragments at Lake Colungulac in Victoria to finally complete the skeletal jigsaw of this enigmatic and controversial marsupial and reveal how nature structured a super carnivore from its ancient herbivorous ancestors,” says Professor Wells.

The study of the first-ever look at complete skeleton of Thylacoleo, Australia’s extinct ‘marsupial lion’, entitled ‘New skeletal material sheds light on the palaeobiology of the Pleistocene marsupial carnivore, Thylacoleo carnifex,‘ has been published in PLOS ONE.