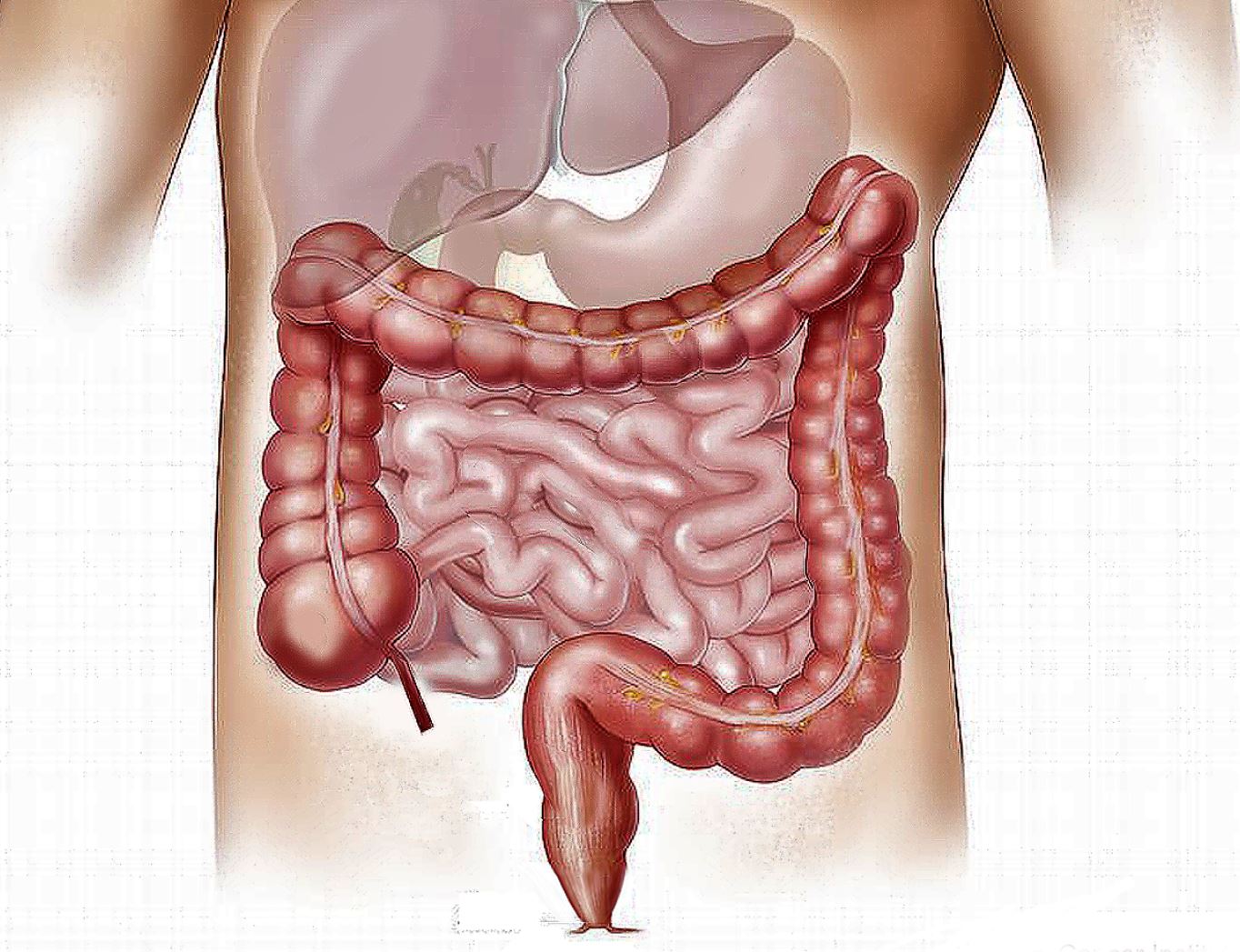

New research led by Flinders has shown for the first time that the gut has a mind of its own, acting independently of the brain and central nervous system.

In fact, this ‘second brain’ in the gastrointestinal tract, may well have been the ‘first brain’ in the evolution of humans.

Flinders University Professor Nick Spencer and fellow researchers in South Australia and the US, have used high-tech methodology to accurately record the nerve activities of the ‘second brain’ in the body.

The scientists used a high-resolution neuronal imaging system and simultaneous electrophysiological recordings from the smooth muscle cells in an isolated whole mouse colon to record the activity of about 400,000 individual neurons in the Enteric Nervous System (ENS).

“The ENS has been called the second brain because it is really a brain of its own, which can function independently of any other neural inputs,” Professor Spencer says.

“Through these experiments, we have been able to see precisely how tens of thousands of individual neurons in the ENS are activated to cause smooth muscle contractions that underlie propulsion of colonic content.

“This is a major mystery in the gut wall.”

It is these contractions that propel waste through the last leg of the digestive system, according to a study of isolated mouse colons published in JNeurosci, an international Society for Neuroscience journal.

Until this study, no one had any idea exactly how large populations of neurons in the ENS led to contractions of the intestine, Professor Spencer says.

“Now we know how the ENS is activated under health conditions and have a blueprint to understand how dysfunctional neurogenic motor patterns may arise along the colon,” he says.

The next step would be to understand how the ENS is activated during chronic constipation, a condition affecting millions of people around the world who rely on medication for relief.

The newly identified neuronal firing pattern may represent an early feature preserved through the evolution of nervous systems.

The enteric nervous system (ENS) is known as the ‘second brain’ or the brain in the gut because it can operate independently of the brain and spinal cord, the central nervous system (CNS). It has also been called the ‘first brain’ based on evidence suggesting that the ENS evolved before the CNS.

Despite the known role of the ENS in generating motor activity in the colon, observing ENS neurons in action has been a challenge.

Professor Nicholas Spencer and colleagues from Flinders University, University of Washington and DST Group in Adelaide, combined a new neuronal imaging technique with electrophysiology records of smooth muscle to reveal a rhythmic pattern of activity underlying so-called colonic migrating motor complexes.

They demonstrate how this activity transports fecal pellets through the mouse colon. These findings identify a previously unknown pattern of neuronal activity in the peripheral nervous system.

Identification of a rhythmic firing pattern in the enteric nervous system that generates rhythmic electrical activity in smooth muscle, by NJ Spender, TJ Hibberd, L Travis, L Wiklendt, M Costa, H Hongzhen, SJ Brookes, DA Wattchow, DJ Keating and J Sorenson has been published in international journal JNeurosci.