The evolution of snakes has some fascinated twists and turns, and new research has found evidence even primitive snakes were adept at living underground and moving through water.

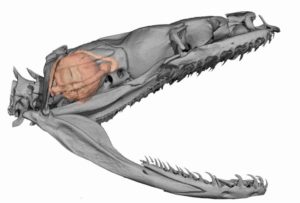

Scientists in South Australia and Canada used CT scans of the inner ear region of a primitive snake called Dinilysia along with 80 species of living snakes and lizards – and found evidence the earliest snakes may have been both eel-like swimmers as well as worm-like burrowers.

“The origin of snakes attracts a lot of controversy and this research helps us have a better understanding of how evolution works,” says Flinders University Biological Sciences research associate in palaeontology Dr Alessandro Palci.

“Their very flexible skulls and extremely elongated bodies are strikingly different from their closest relatives, lizards.

“For well over a century, researchers have vigorously argued whether snakes evolved their long bodies to be better at burrowing (like worms) or at swimming (like eels).

“Our new study suggests that both camps might have been partly right. There are striking resemblances between the inner ear region of the primitive snake Dinilysia and some semi-aquatic snakes, as well as certain burrowing forms.”

“The most primitive snake known, a tiny four-legged creature called Tetrapodophis, seems to have a combination of swimming and burrowing adaptations,” Professor Lee says.

Professor Mike Lee, Flinders University and SA Museum researcher, says his latest Australian Research Council-funded research builds on the idea that primitive snakes frequented both terrestrial and aquatic environments.

“If the ancestral snake was an amphibious burrower, this would explain why so many ancient snakes are aquatic, fossorial, or both. And living snakes continue to excel in those habitats: modern sea snakes are the most rapidly speciating group of reptiles, while the worm-like blindsnakes are found in every continent.”

The paper, The morphology of the inner ear of squamate reptiles and its bearing on the origin of snakes, includes contributions by Associate Professor Mark Hutchinson (SA Museum, Flinders and University of Adelaide School of Biological Sciences) and Professor Michael Caldwell, from the University of Alberta, Canada.

Flinders University’s Palaeontology Laboratory is used for science education and for extensive research into Australia’s megafauna and other prehistoric animals.

The vertebrate palaeontology major introduces students to the study of past life, especially of Australian vertebrates and their environments. It combines topics from Biological Sciences and Environment disciplines to prepare for jobs involving fieldwork and museum studies, as well as ecological and environmental research and teaching.

Students and members of the community can participate in palaeontology (the study of past life) field work and fossil collection with the Flinders University Palaeontology Society.

The SA Museum has a fascinating record of South Australia’s fossil record.

The morphology of the inner ear of squamate reptiles and its bearing on the origin of snakes A Palci, MN Hutchinson, MW Caldwell and MSY Lee, 23 August 2017 Open Science, Royal Society Publishing.