John Long, Flinders University

New South Wales has joined Western Australia to become the second state or territory in Australia to have formally adopted a fossil emblem.

The 365-million-year-old Devonian fish Mandageria fairfaxi was last month announced as the state fossil emblem of NSW.

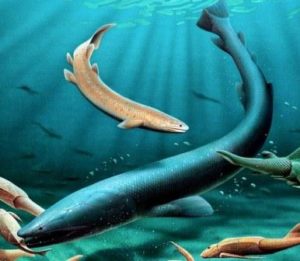

Mandageria was a lobe-finned fish that grew to nearly two metres long. It was a voracious predator with large fangs whose complete fossil remains have been found at the Canowindra fossil site. These can be seen on display at The Age of Fishes Museum in Canowindra.

The selection of the NSW state fossil emblem was driven by key individuals including Dr Alex Ritchie, a former curator in palaeontology of the Australian Museum, who had been working the Canowindra site for many years and found many new species of ancient fishes.

The Geological Survey of NSW officiated the selection of the state fossil, so this process did not involve public input. This contrasts to the very open selection of Australia’s first fossil emblem 20 years ago in WA, which was guided by public submissions.

But why should each state have a fossil emblem anyway?

The importance of fossils

Australian states all have a floral, faunal and marine emblems, representing animals, plants and marine creatures that best epitomise their state’s unique natural history, and they can be used to promote tourism.

The fossil emblem embodies the concepts of deep time and evolutionary transition as being important to understanding the natural history of the particular state.

Fossils add another dimension to understanding our current biodiversity. For example, the numbat is the faunal emblem of WA where it is only found today, although through fossils we know it once lived in NSW and was therefore widespread across the nation.

The idea came from the US where every state has an official state fossil emblem as well as floral, faunal and mineral emblems. The first states to embrace the fossil emblem were Louisiana (petrified palmwood), Maine (the prehistoric plant Pertica quadrifaria) and Georgia (shark tooth), which designated their state fossils in 1976.

Even today it is important to emphasise that teaching evolution is fundamental to understanding biology, as some US states still challenge it. Simply having the states recognise an official fossil emblem was a significant breakthrough for public education in the US.

So when and how did Australia jump on the bandwagon to start recognising fossil emblems?

Fossil emblems for Australia

Australia’s first state fossil emblem was proclaimed on December 5, 1995, as the Devonian fish Mcnamaraspis kaprios, from the 380-million-year-old Gogo sites in WA. I know it well as I discovered it in 1986 and named the fossil in a paper published in 1995.

But I wasn’t the person who selected it to be the emblem. The selection was by a democratic process put in place by the WA government.

The idea came from staff at the Dianella-Sutherland Primary School, in northern Perth, who heard about the US system of having state fossil emblems. The teachers thought the process of lobbying state government to have a state fossil would be an educational exercise for their students. They would learn about local fossils and how governments work.

The students then lobbied the state government and the government listened. Next came a public call for fossils that would fit the bill.

At the time I served as curator of vertebrate palaeontology at the Western Australian Museum. My job was to provide information about various suitable fossils for an emblem to the public, and the arts minister appointed me to chair the State Fossil Emblem Committee.

The school sent a delegation to the museum to see some suitable fossils. They decided that the Gogo fish, Mcnamaraspis, was the one they wanted to support.

The state fossil emblem committee then reviewed nominations received from the public for suitable fossils. The Gogo fish was unanimously selected due to the overwhelming support it received – a petition signed by nearly 1,000 people with numerous supporting letters from international palaeontologists.

The state fossil emblem of WA has been written about in books and used as the topic for a children’s musical play. Symbolised images of it adorned signposts advertising the Kimberley. Later this year we will celebrate its 20-year anniversary.

Fossil emblems for other states and territories

This raises the question: why don’t the other Australian states have their own state fossil emblems? Two of our states are host to world heritage fossil sites – the Naracoorte Caves in South Australia and the Riversleigh sites in Queensland.

With the protection of fossil sites currently under threat in the news in Victoria – the Beaumaris site – the timing for a state fossil emblem campaign couldn’t be better to raise public awareness about fossils and our most important fossil sites.

Victoria has a host of exciting options ranging from the well-preserved early fossil toothed whale such as Janjucetus, very early land plants such as Baragwanathia and superb megafauna such as the Diprotodon. It also has a variety of Cretaceous dinosaurs, a giant amphibian and Australia’s oldest mammals.

Tasmania has several suitable fossil emblems in its very well-preserved Triassic amphibians and reptiles, including the Tasmaniosaurus and several types of giant amphibian.

Muttaburrasaurus (centre) was Australia’s first nearly complete dinosaur skeleton, found in central Queensland. It is one of several fossils suitable to be the fossil emblem of the state.

Queensland has many great contenders among its exciting dinosaurs such such as Muttaburrasaurus or Australovenator. It also has a wealth of diverse and unique fossil mammals including the killer kangaroo Propleopus.

South Australia has the best well-preserved giant fossil kangaroo Procoptodon and the marsupial lion Thylacoleo found at the Naracoorte caves, as well as world famous Ediacaran fossils from the Flinders Ranges (Spriggina, Dickinsonia).

So it’s time to rally and get started if your state or territory doesn’t have a fossil emblem. Schools, lobby your state pollies and get the idea on the drawing board. If Dianella-Sutherland Primary School can make history, so can your school!

John Long, Strategic Professor in Palaeontology, Flinders University

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.