Polluted beaches, oily water, dead birds and marine life destruction caused by crude oil spills could be a thing of the past with pioneering new research led by Flinders University.

An exciting, more sustainable answer to effectively clean up oil spill destruction follows development of a new way to quickly soak up crude oil with an absorbent polymer – itself made from waste products from the petroleum and refining industries.

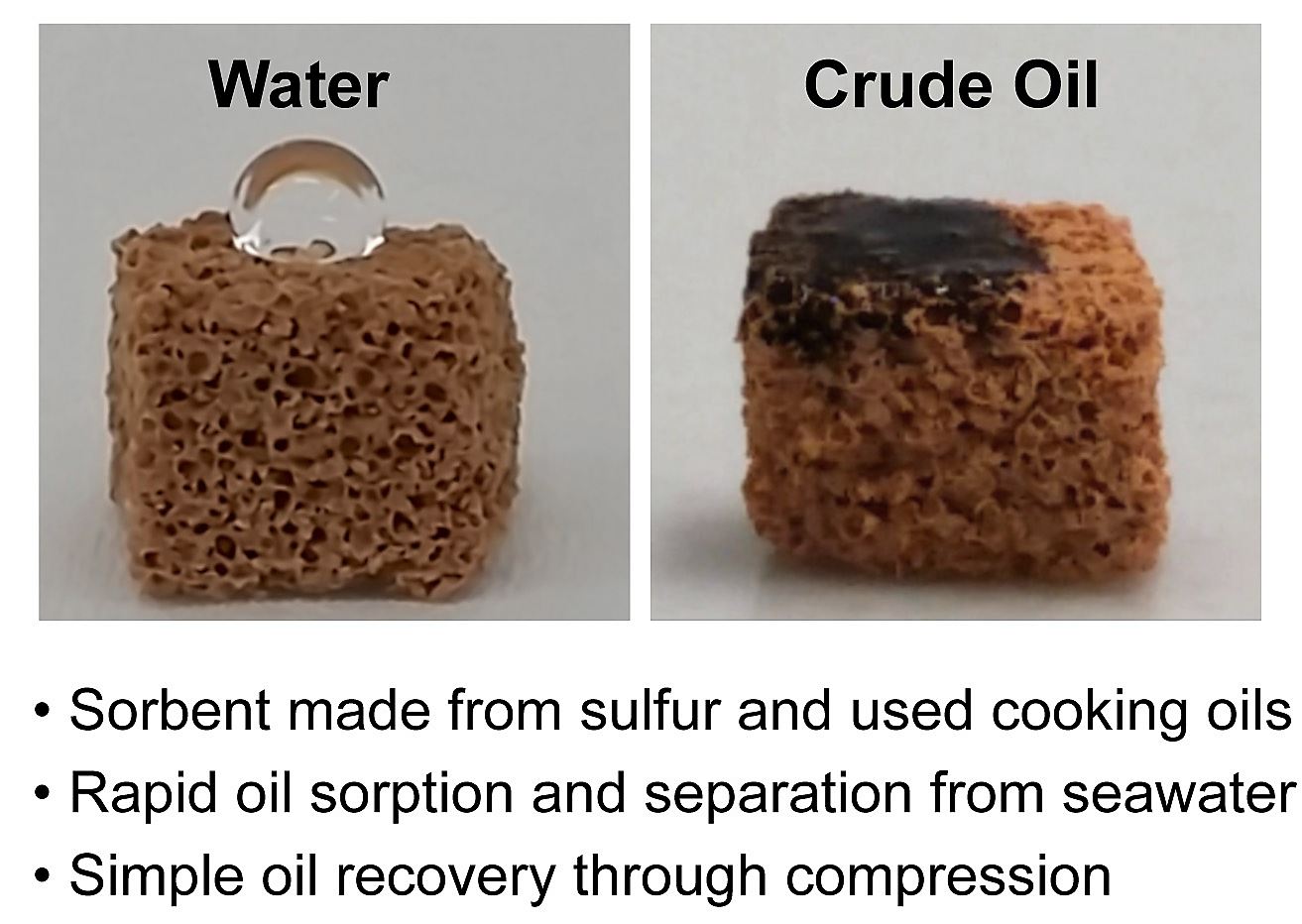

In an environmental win-win, the new type of polymer made from waste cooking oil and sulphur (a by-product of the petroleum industry) has the ability to clean up crude oil and diesel spills.

Better still, because this highly buoyant polymer acts like a sponge to absorb the waste materials from sea water, the polymer can be squeezed to recover the oil and then reused.

Award-winning scientist Dr Justin Chalker, Senior Lecturer in Synthetic Chemistry at Flinders University, is leading an international research team responsible for the discovery.

He is delighted that chemists are finding new ways to provide cheap and effective solutions to curb the damage caused by oil spills, and even mercury in the environment.

“This is an entirely new and environmentally beneficial application for polymers made from sulphur,” says Dr Chalker.

“This application can consume excess waste sulfur that is stockpiled around the globe and may help mitigate the perennial problem of oil spills in aquatic environments.”

Dr Chalker says samples of the new patented polymer have been shipped to potential commercial partners and discussions are under way with several companies that want to test the product in the field.

The Flinders University invention is also registered with Kerafast, a bioscience reagent research register based in Boston in the US, for future development.

Oil spills are a major global issue, with the International Tanker Owners Pollution Federation reporting about 7000 tonnes of crude oil spilling from tankers into oceans in 2017 alone.

A recent large oil spill off Borneo, for example, and prompted Indonesian authorities to declare a State of Emergency.

The international team of researchers point to the effects of recent large-scale spillage catastrophes as a potent reason for their research and potential use in the field – in particular, the explosion on the Deepwater Horizon offshore drilling rig on 20 April 2010 and subsequent release of approximately 4.9 million barrels of crude oil into the Gulf of Mexico.

Hundreds of smaller spills of diesel fuel and other petroleum products affect developing countries in Africa, Asia and South America, for example in the Niger Delta and Amazon basin of Ecuador. The new material made from cheap and sustainable products will help respond to these developing countries where smaller, localised spills threaten groundwater, drinking water and important food staples such as fish.

“This is a new class of oil sorbents that is low-cost, scalable, and enables the efficient removal and recovery of oil from water,” says Dr Chalker.

The research is published in the new paper, Sustainable Polysulfides for Oil Spill Remediation: Repurposing Industrial Waste for Environmental Benefit, published in Advanced Sustainable Systems (Wiley) by Flinders and other researchers – Justin Chalker, Max Worthington, Cameron Shearer, Louisa Esdaile, Jonathan Campbell, Christopher Gibson, Stephanie Legg, Yanting Yin, Nicholas Lundquist, Jason Gascooke, Inês Albuquerque (Instituto de Medicina Molecular, Lisbon), Joseph Shapter (Flinders and University of Queensland), Gunther Andersson, David Lewis and Gonçalo Bernardes (Cambridge University and IMM, Portugal).

The researchers used the common waste substances – canola oil from cooking, sulphur which is a byproduct of the petroleum industry, plus sodium chloride – to create an inexpensive and sustainable sorbent that can mitigate the ecological harm of oil pollution.

Sulphur and cooking oils are hydrophobic, so the new the polymer has an affinity for hydrocarbons such as crude oil and diesel fuel, and can rapidly remove them from seawater.

Laboratory demonstrations of the polymer’s clean-up ability show that absorption of the pollutant happens within a minute of the solution being sprinkled onto oil covering the surface of water.

The research is supported by the Australian Government National Environmental Science Program (NESP), Australian Research Council (ARC), Royal Australian Chemical Institute, Australian Microscopy and Microanalysis Research Facility, Australian National Fabrication Facility, FCT Portugal, The Royal Society, Engineering and Physical Sciences Research Council and European Research Council.

Also see the recent paper, The Mercury Problem in Artisanal and Small-Scale Gold Mining published in Chemistry, A European Journal, (chemeurj.org) explained earlier in Flinders news.