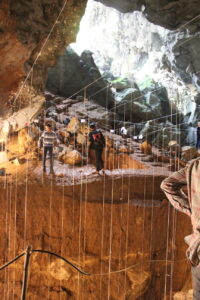

What connects a fossil found in a cave in northern Laos with stone tools made in north Australia? The answer is, we do. When our early Homo sapiens ancestors first arrived in Southeast Asia on their way from Africa to Australia, they left evidence of their presence in the form of human fossils that accumulated over thousands of years deep in a cave.

The latest evidence from Tam Pà Ling cave in northern Laos, uncovered by a team of Laotian, French, American and Australian researchers and published in Nature Communications, demonstrates beyond doubt that modern humans spread from Africa through Arabia and to Asia much earlier than previously thought.

It also confirms that our ancestors didn’t just follow coastlines and islands. They travelled through forested regions, most likely along river valleys, too. Some then moved on through Southeast Asia to become Australia’s First People.

“Tam Pà Ling plays a key role in the story of modern human migration through Asia but its significance and value is only just being recognised,” says University of Copenhagen palaeoanthropologist Assistant Professor Fabrice Demeter, one of the paper’s lead authors.

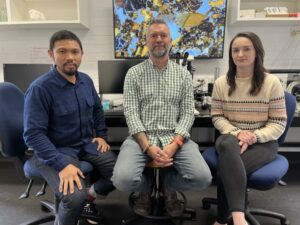

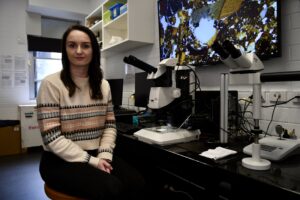

Three Australian Universities contributed to the project. The researchers at the Flinders Microarchaeology Laboratory showed that the sediment in the cave had been laid down in distinct layers over tens of thousands of years.

“Far from reflecting a rapid dump of sediments…” says geoarchaeologist, Associate Professor Mike Morley from Flinders University, working with Flinders PhD students Vito Hernandez and Meghan McAllister-Hayward, “…the site represents a consistent and seasonally deposited stack of sediments.

The Flinders Microarchaeology Laboratory researchers supported the dating evidence with a detailed analysis of the sediments to assess the origin of the fossils.

They used a number of techniques including micromorphology, which examines sediments under a microscope to establish the integrity of the layers. This key component of the new chronology helped establish that there was a fairly consistent accumulation of sedimentary layers over a long period.

“The results of our microarchaeological analyses have drawn for us a better appreciation of the ground conditions in Tam Pà Ling in the past, therefore allowing for more precise interpretations of how and when these early modern human fossils were buried in this part of the cave,” says PHD Student, Vito Hernandez.

“It gives us great pride and joy to be part of a laboratory that is exploring and using cutting edge techniques in archaeological science and contributing to a greater understanding of the prehistory of modern humans in the Australasian region!” says PHD Student and 2021 International Student Awards winner Meghan McAllister-Hayward.

Since the first excavation and the discovery of a skull and mandible in 2009, the cave has been controversial. Evidence of our earliest journeys from Africa into Southeast Asia is usually dominated by island locations such as Sumatra, Philippines and Borneo.

This was before Tam Pà Ling, an upland cave site more than 300 kilometres from the sea in northern Laos, started divulging its secrets. The skull and jawbone were identified as belonging to Homo sapiens who had migrated through the region. But when?

As is usual in questions of human dispersal, the debate comes down to timing. But this evidence was hard to date.

The human fossils cannot be directly dated as the site is a World Heritage area and the fossils are protected by Laotian law. There are very few animal bones or suitable cave decorations to date, and it is too old for radiocarbon dating. This placed a heavy burden on the luminescence dating of sediments to form the backbone of the timeline.

Luminescence dating relies on a light-sensitive signal that is reset to zero when exposed to light but builds up over time when shielded from light during burial. It was originally used to constrain the burial sediments that encased the fossils.

“Without luminescence dating this vital evidence would still have no timeline and the site would be overlooked in the accepted path of dispersal through the region,” says Macquarie University geochronologist Associate Professor Kira Westaway. “Luckily the technique is versatile and can be adapted for different challenges.”

These techniques returned a minimum age of 46,000 years – a chronology in line with the expected timing of Homo sapiens’ arrival in Southeast Asia. But the discovery didn’t end here.

From 2010 to 2023, annual excavations (delayed by three years of lockdowns) revealed increasingly more evidence that Homo sapiens had passed through en route to Australia.

Seven pieces of human skeleton were found at intervals through 4.5 metres of sediment, pushing the potential timeline far back into the realms of the earliest Homo sapiens migrations to this region.

In this study, the team overcame these issues by creatively applying strategic dating techniques where possible, such as the uranium-series dating of a stalactite tip that had been buried in sediment, and the use of uranium-series dating coupled with electron-spinresonance dating techniques to two rare but complete bovid teeth, unearthed at 6.5 metres.

“Having direct dating of the fossil remains confirmed the age sequence obtained by luminescence, allowing us to propose a comprehensive and secure chronology for a Homo sapiens presence at Tam Pà Ling,” says Southern Cross University geochronologist Associate

Professor Renaud Joannes-Boyau. The team supported the dating evidence with a detailed analysis of the sediments to assess the origin of the fossils using micromorphology, a technique that examines sediments under a microscope to establish the integrity of the layers. This key component of the new chronology helped establish that there was a consistent accumulation of sedimentary layers over a long period.