A rare fossil discovery by Flinders University researchers illuminates the ultimate survival test faced by Genyornis newtoni, the last of Australia’s famous giant birds – the dromornithids or ‘Thunder Birds’ – just before they went extinct.

The remarkable find, published in the journal Papers in Palaeontology, describes severe bone infections in several fossil remains of Genyornis, found mired in the 160 km2 salt lake beds of SA’s Lake Callabonna fossil reserve, about 600 km northeast of Adelaide.

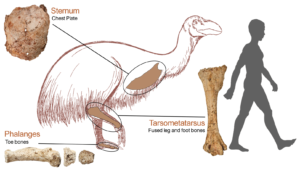

The giant Genyornis weighed around 230 kg – 5 to 6 times that of an emu – and stood about 2 m tall.

This new research shows that getting stuck in the treacherous muddy bed of Lake Callabonna was not the only concern facing Genyornis. Some also had a painful bone disease which Flinders University researcher and lead author on the paper, Phoebe McInerney, says would have hampered their mobility and foraging.

“The fossils with signs of infection are associated with the chest, legs and feet of four individuals. They would have been increasingly weakened, suffering from pain, making if difficult to find water and food,” she says.

“It’s a rare thing in the fossil record to find one, let alone several, well-preserved fossils with signs of infection. We now have a much greater idea of the life challenges of these birds.”

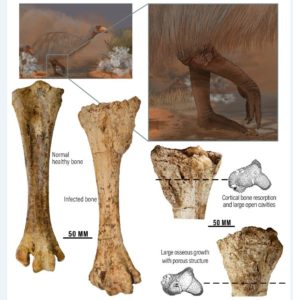

The study found about 11% of the birds were suffering from osteomyelitis, a severe bone infection. “We see frothy and woven bone, large abnormal growths and cavities in their fossil remains,” Miss McInerney explains.

Finding multiple individuals in the population with osteomyelitis is unusual among all birds. This suggests that a more complex situation may have caused this phenomenon.

University of Adelaide co-author, Associate Professor Lee Arnold, dated the lake sediments in which Genyornis was found. This links the deaths of these individuals with a period of severe drought beginning about 48,000 years ago.

During this drought, these giant birds, along with other megafaunal species, including the ancient giant relatives of the wombats and kangaroos, were facing major environmental challenges.

As the landscape dried across Australia, the large inland lakes and forests began to disappear, and central Australia became flat desert plains now covered by lakes of salt.

“As the drought conditions worsened, food resources would have been reduced, placing considerable stress on the animals”, says co-author Associate Professor Trevor Worthy, from Flinders University’s Palaeontology Laboratory.

“From studies on living birds, we know that challenging environmental conditions can have negative physiological effects, so we infer that the Lake Callabonna population of Genyornis would have been struggling through such conditions,” he says.

It now appears that the effects of severe drought phases included high rates of bone infection in the Lake Callabonna population. Weakened individuals were more likely to become mired in the deep muds of Lake Callabonna and die.

With no conclusive evidence to suggest that Genyornis newtoni survived much past this time, it is likely that protracted drought and high disease rates may have contributed to this species eventual extinction. “We now know more about the lives and deaths of these birds compared to 125 years ago when they were first described,” Miss McInerney concludes.

The article, ‘Multiple occurrences of pathologies suggesting a common and severe bone infection in a population of the Australian Pleistocene giant, Genyornis newtoni (Aves, Dromornithidae)’ 2021 by PL McInerney, LJ Arnold, C Burke, AB Camens, and TH Worthy has been published in the international peer-reviewed journal Papers in Palaeontology DOI: 10.1002/spp2.1415.

Read more in The Conversation.