As the world waits anxiously for a vaccine to fight COVID-19, 30 former COVID-19 positive patients have gifted their blood to Flinders researchers in a bid to find ‘super-antibodies’ to use as a weapon to beat the virus.

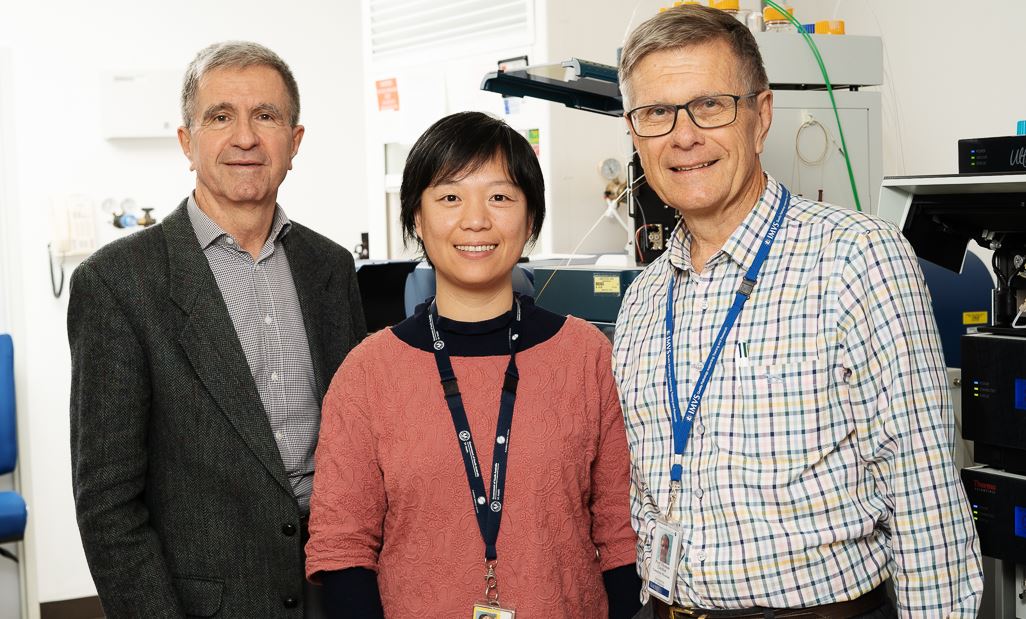

The research team, which includes lead scientist Dr Jing Jing Wang, Professor David Gordon and Professor Tom Gordon, are working to ‘fingerprint’ the repertoire of antibodies that develop following the disease.

Armed with this knowledge, the team hopes to pinpoint the most important ‘super-antibodies’ to help create long-term immunity to future virus infection, and follow their levels in individual patients over time.

This research is one of eight projects to receive funding from Flinders Foundation and Flinders University to make new discoveries into COVID-19. They are running parallel with many more COVID-19 research projects underway at Flinders.

The work involves identifying and purifying the COVID-19 specific antibodies from blood and determining their protein sequences using a technique called mass spectrometry, collaborated with Dr Tim Chataway, from the Flinders Proteomics Facility.

“Blood antibodies are the most effective weapons to beat COVID-19,” Professor Tom Gordon said. “We are fortunate in being able to collaborate with researchers at the Doherty Institute in Melbourne on this project”.

“The technology we’ve developed here can break down the composition of antibodies which leads to a more meaningful diagnostic test to analyse people infected with COVID-19.

“We’ll be able to tell how well newly developed vaccines are working, by monitoring the level of change in these specific antibodies after natural virus infection compared with the immune response following vaccination….with the aim of finding those antibodies the vaccine should be steered towards.”

The combined Flinders University and SA Pathology research team has already applied their technology to other infectious diseases and vaccines, but like many researchers, the team focussed its expertise on COVID-19 when it struck.

Infectious Diseases specialist Professor David Gordon, who cared for many of the patients who tested positive at Flinders Medical Centre’s COVID-19 Testing Clinic, says he is grateful to the 30 patients for volunteering to provide their blood for the research.

“These people are incredibly valuable because they clearly have the antibodies that worked, because they all got better,” he says. “Every single person we asked has been so cooperative and happy to help.”

For one of the 30 blood donors, it was an easy decision to contribute towards this world-class research. “It’s a big unknown and we need to find answers, so if they can use me, I’ll do anything to help,” Di Keogh, says 63, who caught the virus aboard the Ruby Princess cruise ship. “We were taken such good care of while isolating at home, nurses visited us at home and doctors rang every day to ask how we were and we were given a number to call if ever we needed – they were lovely.”

Funds raised through Flinders Heroes is helping frontline healthcare workers and researchers.

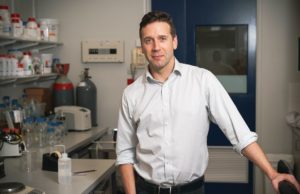

SAHMRI and College of Medicine and Public Health Professor Geraint Rogers is one of the other projects funded by the Flinders Foundation ‘Flinders Heroes‘ campaign and Flinders University to make new discoveries into COVID-19.

This study is exploring precision antibiotic strategies to tackle the two areas of greatest concern in the fight against COVID-19.

By looking at precision antibiotic care tailored to individual patients, Professor Geraint Rogers’ work seeks to address the development of acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS) – the principal cause of COVID-19 related deaths and the associated demand for ventilators and intensive care unit (ICU) beds.

“Patients who develop severe respiratory disease following infection require hospitalisation, and ultimately ventilation and intensive care. These patients are at high risk of bacterial respiratory infections and often receive antibiotics,” Professor Rogers says.

“However, the type of antibiotics, the way they are delivered, and their timing all vary considerably between clinicians and intensive care units, and there is no clear evidence base to guide their use.”

While invasive mechanical ventilation can be a critically important for severely ill COVID-19 patients, it also has substantial risks.

“The longer patients require ventilation, the greater the likelihood of adverse outcomes, including secondary infection and the development of ARDS,” Professor Rogers says.

“In addition, because there is a limited number of ICU beds, the longer any one patient requires ventilation, the less capacity we have to treat others … where this has occurred elsewhere in the world, the consequences have been dire.

“The ultimate aim of our work is to provide a basis for precision antibiotic care, tailored to the clinical needs of individual COVID-19 patients with severe respiratory disease,” he says.