Researchers have identified 107 genes that increase a person’s risk of developing the eye disease glaucoma, and now developed a genetic test to detect those at risk of going blind from it.

The research, led by Flinders University and QIMR Berghofer Medical Research Institute, has been published in the international Nature Genetics journal.

In a world first, genetic information from tens of thousands of people around the world has been used to develop a test to identify individuals at risk of developing glaucoma, the leading cause of irreversible blindness globally.

The new predictive test means glaucoma, which affects about 76 million people worldwide, can be more accurately predicted using a single blood or saliva sample.

Once accredited for use, the test will improve doctors’ ability to predict and prevent vision loss from glaucoma. It will also guide the age at which screening for glaucoma should start, and the level of risk to other family members.

The researchers are now hoping to recruit 20,000 people with a personal or family history of the disease to join the Genetics of Glaucoma study so they can identify more genes that play a role in the condition.

“Glaucoma is a genetic disease and the best way to prevent the loss of sight from glaucoma is through early detection and treatment,” says Associate Professor Stuart MacGregor, head of QIMR Berghofer’s Statistical Genetics Group and co-lead author on the new paper.

“Our study found that by analysing DNA collected from saliva or blood, we could determine how likely a person was to develop the disease and who should be offered early treatment and or monitoring.

“Importantly, unlike existing eye health checks based on eye pressure or optic nerve damage, the genetic test can be done before damage begins so regular screening can be put in place.

“Having a high risk score doesn’t mean you will definitely get glaucoma, but knowing you could be at future risk allows people to take the necessary precautions.”

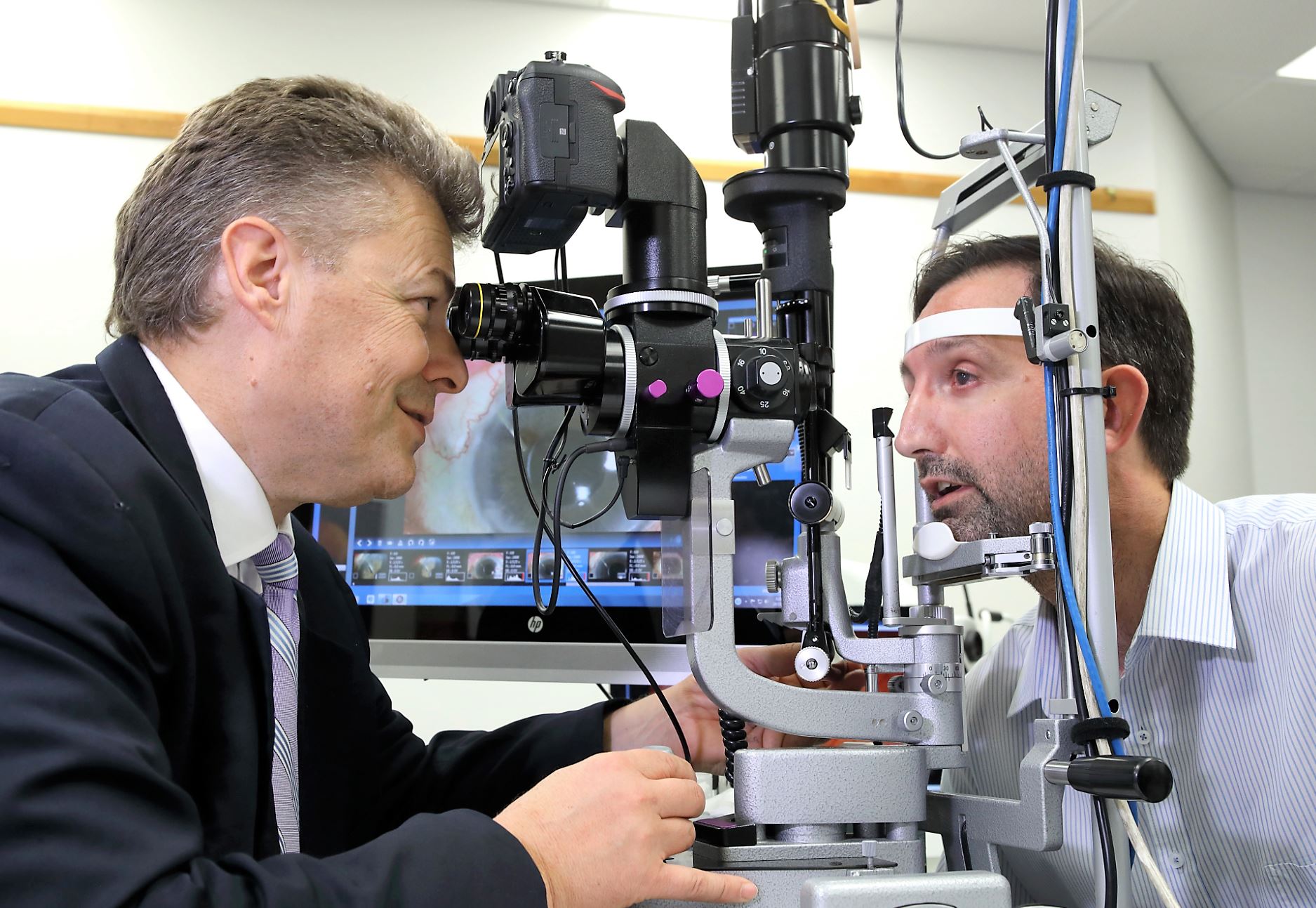

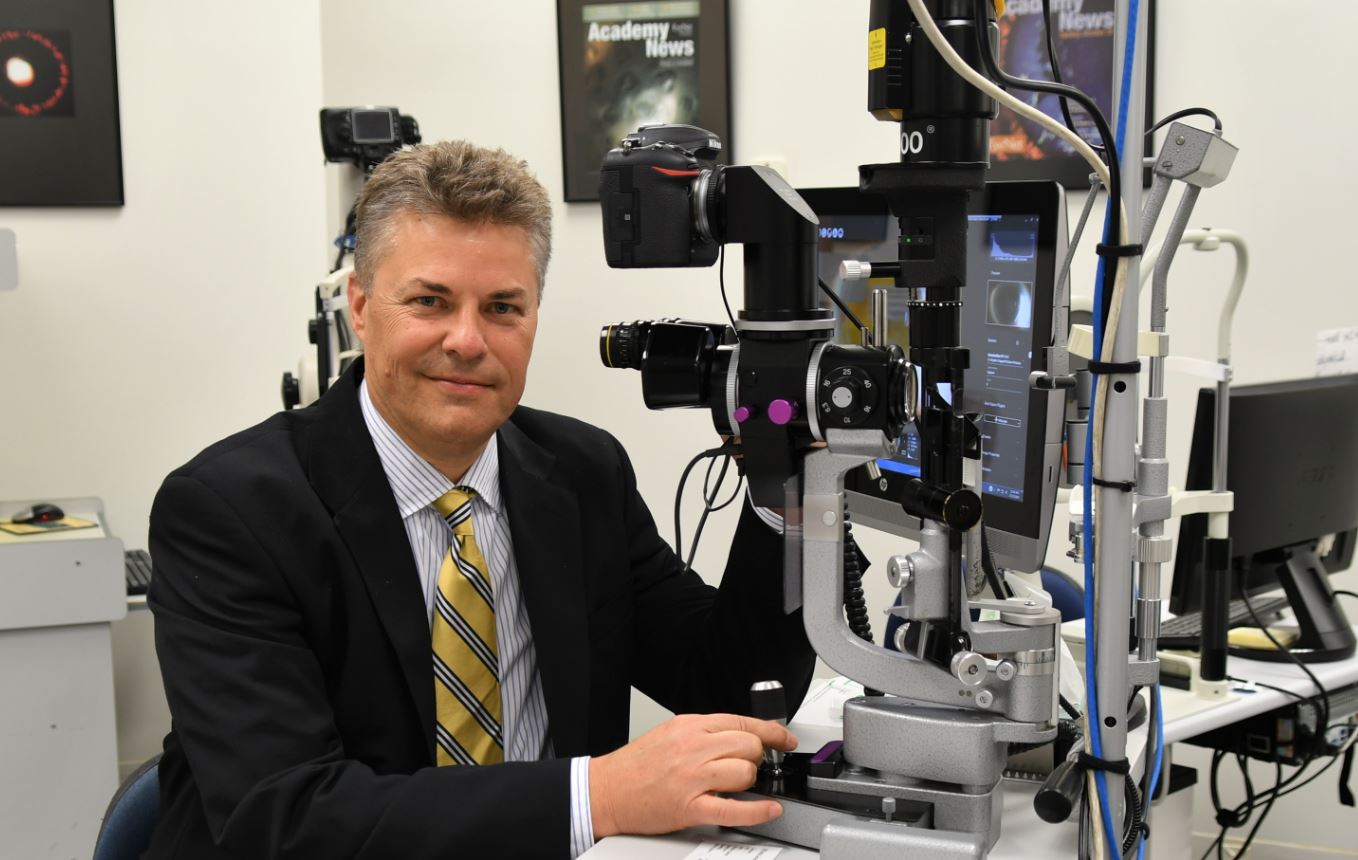

Clinical lead researcher and Chair and Academic Head of Ophthalmology at Flinders University, Professor Jamie Craig, says the study results provides hope that mass screening for glaucoma could be offered in the future.

“There are Australians who, if they’d had appropriate treatment a few years earlier, wouldn’t have gone blind,” says Professor Craig, who is also a consultant ophthalmologist.

“One in 30 Australians has glaucoma, but most people only find out they have it when they go to the optometrist because they are losing vision, or for a general eye check.

“Early detection is paramount because existing treatments can’t restore vision that has been lost, and late detection of glaucoma is a major risk factor for blindness.

“Glaucoma can arise at any age but most of those affected are in their 50s or older, so our ultimate aim is to be able to offer blood tests to people when they turn 50 so they can find out if they are at risk, and then hopefully act on it.

“In most cases, glaucoma can be treated easily using simple eye drops, but this test is likely to be helpful in identifying those who would benefit from more aggressive intervention such as surgery.”

“There is no single definitive test for glaucoma, and diagnosis involves assessing a range of features including visualising the optic nerve and testing peripheral vision,” says Professor Craig, a senior NHMRC practitioner and research leader at Flinders.

“With these results, we can now quite accurately assess an individual’s genetic risk ‘score’ for developing glaucoma, similar to other tests in development for cardiovascular disease, breast and bowel cancer.”

Early detection of glaucoma is paramount because existing treatments are unable to restore vision once it’s lost, and late presentation is a major risk for blindness.

Early diagnosis makes it much easier to maintain good vision using a range of treatments, he says, and people with high genetic risk scores are more likely to need invasive treatments such as surgery to control their disease.

The research has been funded by the National Health and Medical Research Council (NHMRC).

The paper, ‘Multitrait analysis of glaucoma identifies new risk loci and enables polygenic prediction of disease susceptibility and progression’ (2020) by JE Craig, X Han, A Qassim, M Hassall, JN Cooke Bailey, TG Kinzy, AP Khawaja, J An, H Marshall, P Gharahkhani, RP Igo Jr, SL Graham, PR Healey, JS Ong, T Zhou, O Siggs, MH Law, E Souzeau, B Sheldrick, PG Hysi, KP Burdon, RA Mills, J Landers, JB Ruddle, A Agar, A Galanopoulos, AJR White, CE Willoughby, N Andrew, S Best, AL Vincent, I Goldberg, G Radford-Smith, NG Martin, GW Montgomery, V Vitart, R Hoehn, R Wojciechowski, JB Jonas, T Aung, LR Pasquale, AJ Cree, S Sivaprasad, NA Vallabh, NEIGHBORHOOD Consortium, UK Biobank Eye and Vision Consortium, AC Viswanathan, F Pasutto, JL Haines, CCW Klaver, CM van Duijn, RJ Casson, PJ Foster, P Tee Khaw, CJ Hammond, DA Mackey, P Mitchell, AJ Lotery, JL Wiggs, AW Heritt and S MacGregor has been published in Nature Genetics (Nature Publishing). DOI: 10.1038/s41588-019-0556-y