New insights into how the colon functions and actually expels its contents have been revealed for the first time following decades of study by Flinders University researchers.

It promises new diagnostics tools and treatments for gastrointestinal disorders to address problems with bowel movements leading to constipation, diarrhoea and pain, affecting hundreds of millions of people worldwide.

Propulsion of intestinal contents is controlled by millions of neurons within the wall of the gut, known as the enteric nervous system. Capable of operating independently of the brain, a functioning enteric nervous system is essential for life – but exactly how it functions has been a mystery.

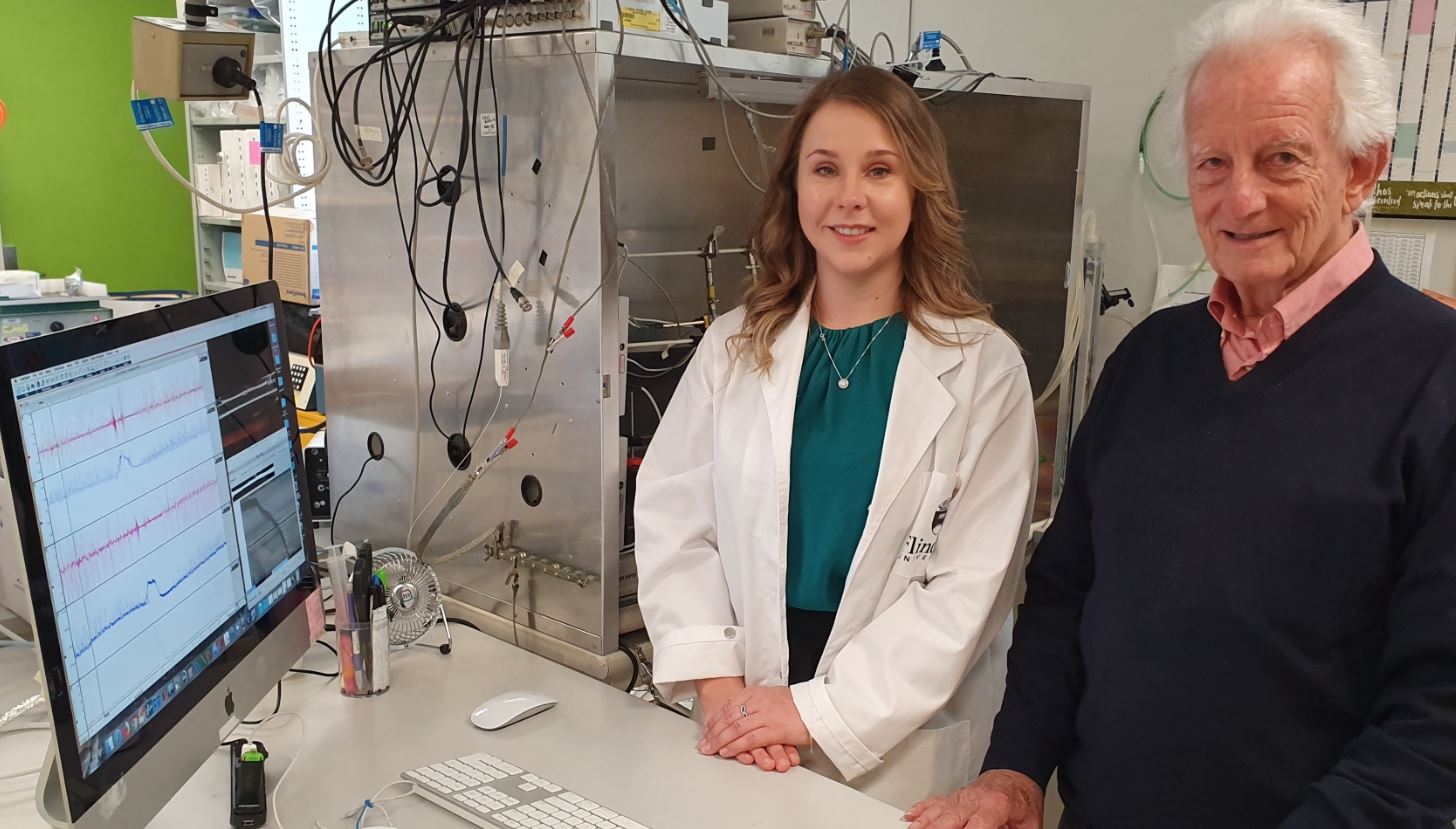

By unravelling the neural circuits of the enteric nervous system in guinea pigs and humans Professor Marcello Costa and colleagues are able to understand how the enteric nervous system ensures that food is slowly mixed and propelled along the digestive tube, allowing for absorption of nutrients and excretion of waste.

“For the first time we have combined video recording intestinal movements with a pressure-measuring manometric probe, enabling movements, pressures and electrical activities to be recorded all at the same time within the colon,” Professor Costa says.

“This powerful combination of techniques applied to a guinea pig colon identified several distinct neural mechanisms involved in the propulsion of colonic contents. This answers the deceptively simple question of how neural mechanisms within the colon manage the propulsion of bowel contents,” he says.

“The findings also show how studies in human and animals can be complementary, identifying fundamental mechanisms that are shared across species – in this case guinea pigs and humans.

“Currently we treat intestinal disorders by addressing the symptoms, such a stopping-up diarrhoea or softening stools to ease constipation, but as a result of this new understanding of the neural networks of the enteric system, clinicians may be able to develop treatments that treat the cause of the problems,” Professor Costa says.

The paper, Roles of three distinct neurogenic motor patterns during pellet propulsion in guinea pig distal colon (DOI 10.1113/JP278284) is Professor Costa’s 276th publication and is featured on the cover of the prestigious Journal of Physiology.

Background

The ideas behind this paper date back to the mid 1970s when Flinders University physiologist Professor Marcello Costa and anatomist John Furness began to investigate how the enteric nervous system allows the colon manages to propel pellets in the right direction. They established this fundamental motor behaviour can be studied in isolated segments of intestine, which could be kept alive in organ baths.

The tantalising possibility that neural circuits entirely contained within the gut wall could control the complex motor behaviour of the intestine, led to pioneering studies at Flinders in the 1980s. A team consisting of a newly qualified surgeon, Professor David Wattchow, one of the first graduates in medicine at Flinders, joined Professor Costa and his colleague Professor Simon Brookes on a quest to unravel the neural circuits of the enteric nervous system in both guinea pigs and ultimately humans.

This collaboration grew and formed the basis of the current study. There are now four independent ‘Neurogastroenterology’ laboratories at Flinders, led by Professors Nick Spencer, Simon Brookes, Taher Omari and Phil Dinning , with Professor Costa a guest researcher in all. Together, they have now been able to answer the deceptively simple question of how neural mechanisms within the colon generate the appropriate controlled propulsion of colonic contents.

A method using video recordings to study intestinal movements was developed twenty years ago by Professor Costa and a PhD student. Recently, this was combined with a manometric (pressure sensing) probe, developed for studying colonic behaviour in human subjects by Engineering Professor John Arkwright and Senior Medical Scientist Associate Professor Phil Dinning. The pair received the coveted Eureka Prize for this method in 2011.

Here, Professor Costa used it to study the isolated guinea pig colon, so that movements, pressures and electrical activities could be recorded; all at the same time. This powerful combination of techniques identified several distinct neural mechanisms involved in the propulsion of colonic contents.

The Flinders labs are having a strong influence in the world of clinical gastroenterology. They organised an international Consensus Meeting in 2016. From this, an important Consensus Paper just been published in the influential journal Nature Reviews in Gastroenterology and Hepatology about the different patterns of colonic behaviour in animals and humans. Other work led by Professors Nick Spencer and David Wattchow has shown that isolated segments of human colon show similar types of behaviour to animal studies.

Studies of the human enteric nervous system are well supported at Flinders by grants from the Australia’s National Health and Medical Research Council (NHMRC) and from the National Institutes of Health (USA). Related studies on the gastrointestinal tract of laboratory animals is also well supported by competitive funding from the NHMRC and Australian Research Council.

The paper by Professor Costa and colleagues is the fruit of long-standing interdisciplinary collaborations between the Flinders ‘Neurogastroenterology’ labs. It shows how studies in human and animals can be complementary, identifying fundamental mechanisms that are shared across species. The similarities between neural mechanisms of intestinal motility experimental animals and human paves the way for further research to develop animals models of functional diseases in humans and the novel combined techniques developed at Flinders improve diagnosis of intestinal motor disorders.