One third of the world’s population is infected with the Toxoplasma parasite– which causes a common eye infection called ocular toxoplasmosis.

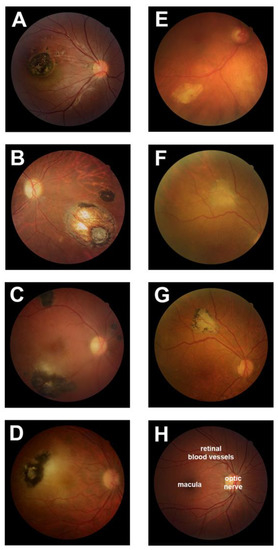

Researchers have now shed light on how the infection causes a distinctive lesion in the retina.

An international research team, from Flinders University and University of São Paulo in Brazil, have identified proteins produced from infected retinal cells that push neighbouring uninfected retinal cells to overgrow and create a distinctive lesion that doctors can use to diagnose the infection.

This breakthrough study –published in Microorganisms– is the first to use laboratory methods to understand how Toxoplasma infection leads to a characteristic eye lesion, after researchers monitored the process at a Brazilian eye clinic serving a region of 1.7 million people.

Flinders Strategic Professor in Eye & Vision Health and Superstar of STEM, Justine Smith, says the research demonstrates how retinal cells respond to an infection with Toxoplasma, and shows that the cell response may help parasites spread through the retina.

“In one of the largest groups of people with ocular toxoplasmosis studied to date, we see that infection causes a typical lesion in over 90% of infected eyes,” says Professor Smith.

“Our findings show that T. gondii-infected human retinal pigment cells secrete VEGF and IGF1, and reduce production of TSP1, which promotes the proliferation of uninfected cells and renders those cells more susceptible to infection as a result.”

Co-Investigator from University of São Paulo and the International Agency for Prevention of Blindness, Dr Joao Furtado, speculates that manipulating proteins within the eye might have therapeutic applications to limit the severity of the disease.

“There is no cure for toxoplasmosis, which is most often food borne. The World Health Organisation recommends food safety measures that include hand-washing, use of clean water in food preparation, and proper cooking,” says Dr. Furtado.