Extended parental care is considered one of the hallmarks of human evolution. A stunning new research result published in the prestigious journal Nature reveals for the first time the parenting habits of one of our earliest extinct ancestors.

Analysis of more than two-million-year-old teeth from Australopithecus africanus fossils found in South Africa have revealed that infants were breastfed continuously from birth to about one year of age.

Nursing appears to continue in a cyclical pattern in the early years for infants; seasonal changes and food shortages caused the mother to supplement gathered foods with breastmilk.

The research was conducted by an international team led by Dr Renaud Joannes-Boyau of Southern Cross University, along with Dr Luca Fiorenza and Dr Justin W. Adams from Monash University, and supported by Dr Ian Moffat at Flinders University.

“For the first time, we gained new insight into the way our ancestors raised their young, and how mothers had to supplement solid food intake with breastmilk when resources were scarce,” said geochemist Dr Joannes-Boyau from the Geoarchaeology and Archaeometry Research Group (GARG) at Southern Cross University.

“These finds suggest for the first time the existence of a long-lasting mother-infant bond in Australopithecus. This makes us to rethink on the social organisations among our earliest ancestors,” said Dr Luca Fiorenza, who is an expert in the evolution of human diet at the Monash Biomedicine Discovery Institute (BDI).

“Fundamentally, our discovery of a reliance by Australopithecus africanus mothers to provide nutritional supplementation for their offspring and use of fallback resources highlights the survival challenges that populations of early human ancestors faced in the past environments of South Africa,” said Dr Justin Adams, an expert in hominin palaeoecology and South Africa sites.

For decades there has been speculation about how early ancestors raised their offspring. With this study, the research team has opened a new window into our enigmatic evolutionary history.

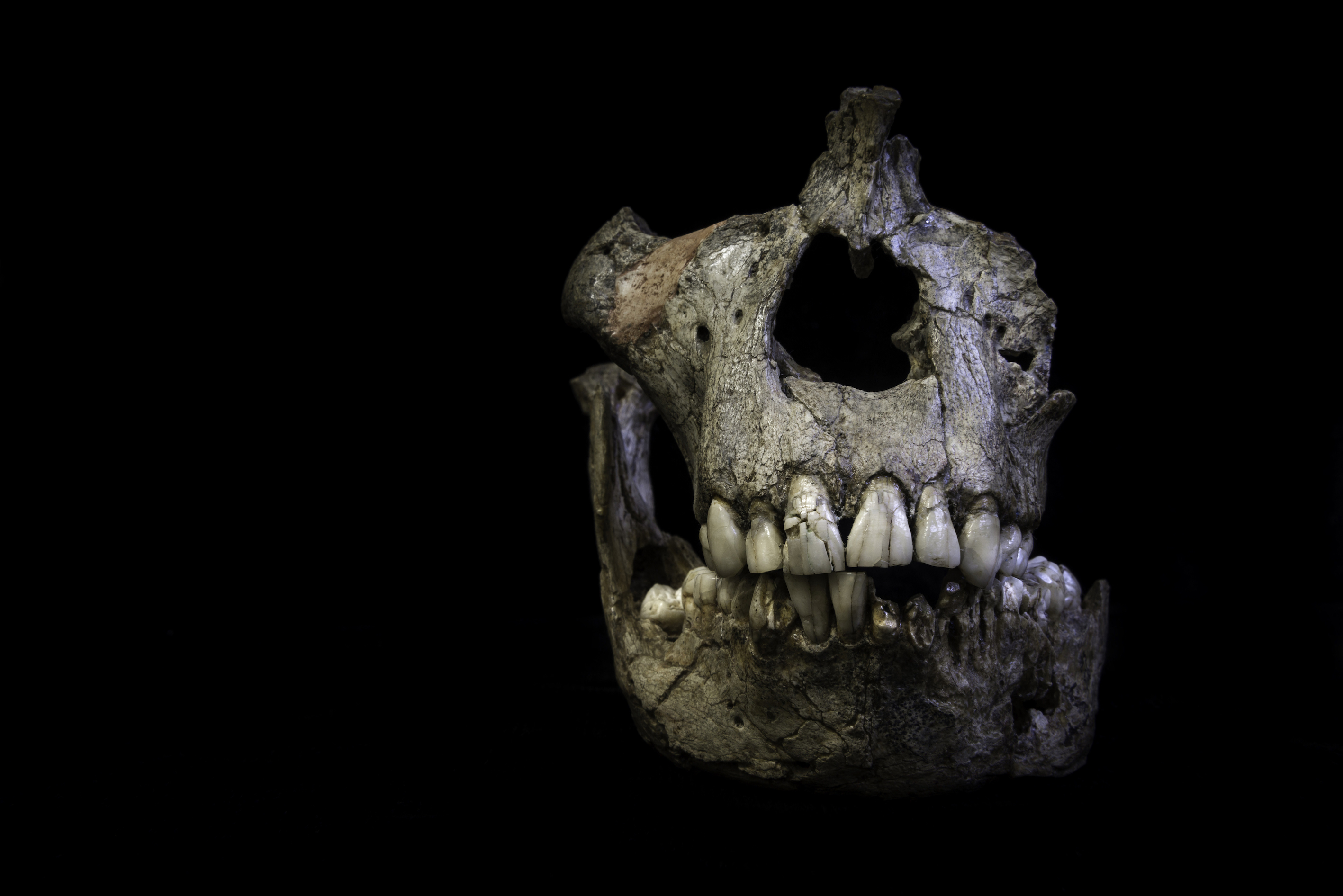

Australopithecus africanus lived from about two to three million years ago during a period of major climatic and ecological change in South Africa, and the species was characterised by a combination of human-like and retained ape-like traits.

While the first fossils of Australopithecus were found almost a century ago, scientists have only now been able to unlock the secrets of how they raised their young, using specialised laser sampling techniques to vaporise microscopic portions on the surface of the tooth.

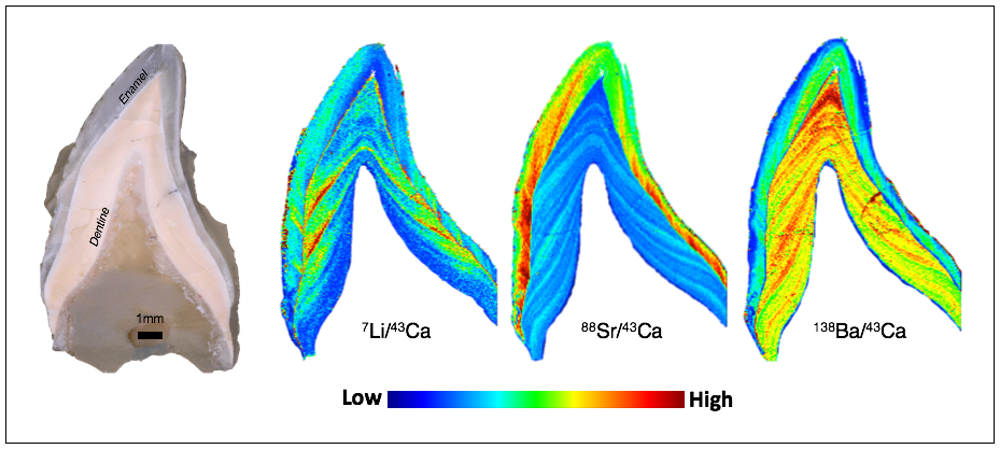

The gas containing the sample is then analysed for chemical signatures with a mass spectrometer– enabling researchers to develop microscopic geochemical maps which can tell the story of the diet and health of an individual over time.

Dr Ian Moffat said this study mapped changes in the concentration of barium, strontium and lithium across a range of fossil teeth to understand the maternal behaviour of the species.

“The concentration of these elements in our bodies can change significantly depending on our diet and these changes are reflected in the composition of our bones and teeth.

“Teeth are wonderful time capsules of what you eat when you are a child. While our bones continue to change composition as they remodel during our lives, once our teeth mineralise and are fully formed they don’t change composition so they perfectly capture our childhood diet.

“We found this hominid used an extended period of breastfeeding for about a year and a half, and after that they supplemented breast milk with solid food depending on the availability of resources in the landscape, maybe up to 5 or 6 years. I think this speaks to the possibility of this fossil being a transitional species, and it’s an entirely new line of evidence to understand how this fossil fits into our human evolutionary lineage” he said.

Teeth grow similarly to trees; they form by adding layer after layer of enamel and dentine tissues every day. Thus, teeth are particularly valuable for reconstructing the biological events occurring during the early period of life of an individual, simply because they preserve precise temporal changes and chemical records of key elements incorporated in the food we eat.

By developing micro geochemical maps, it’s possible to ‘read’ successive bands of daily signal in teeth, which provide insights into food consumption and stages of life.

Previously the team had revealed the nursing behaviour of our closest evolutionary relatives, the Neanderthals. With this latest study, the international team has analysed teeth that are more than ten times older than those of Neanderthals.

“We can tell from the repetitive bands that appear as the tooth developed that the fall back food was high in lithium, which is believed to be a mechanism to reduce protein deficiency in infants more prone to adverse effect during growth periods,” Dr Joannes-Boyau said.

“This likely reduced the potential number of offspring, because of the length of time infants relied on a supply of breastmilk. The strong bond between mothers and offspring for a number of years has implications for group dynamics, the social structure of the species, relationships between mother and infant and the priority that had to be placed on maintaining access to reliable food supplies,” he said.

“This finding underscores the diversity, variability and flexibility in habitats and adaptive strategies these australopiths used to obtain food, avoid predators, and raise their offspring,” Dr Adams emphasised.

“This is the first direct proof of maternal roles of one of our earliest ancestors and contributes to our understanding of the history of family dynamics and childhood,” concluded Dr Fiorenza.

The team will now work on species that have evolved since, to develop the first comprehensive record of how infants were raised throughout history.

Read more in The Conversation, or the full paper in Nature titled Elemental signatures in Australopithecus africanus teeth reveal seasonal dietary stress.