One hundred years ago – on November 11 1918, at the 11th hour of the 11th day of the 11th month – millions of men laid down their guns.

This was Armistice Day, the end of the first world war.

Germany, the last belligerent standing among the Central Powers, had collapsed militarily, economically and politically.

Armistice Day – later known as Remembrance Day – has since been commemorated every year.

Lecturer in Australian History, Dr Romain Fathi, recounts the history of Remembrance Day over the past century.

Ending the war

On November 11 1918, aboard Marshall Ferdinand Foch’s train carriage, a few plenipotentiaries of Germany and the main Allied nations signed a short document that ordered a ceasefire, effective from 11am. In doing so, they put an end to the global carnage that had started in August 1914 and had killed more than 10 million combatants and 6 million civilians.

Notably, though this document stopped combat, it did not formally end the war. Indeed, Germany had sought an armistice in order to negotiate a formal peace treaty. This peace was secured eight months later, on June 28 1919, at the Paris Peace Conference.

The Armistice also didn’t resolve localised conflicts resulting from the war. These raged on in parts of Eastern Europe and the Middle East through to the early 1920s.

But for most nations involved in the first world war, the armistice of November 11 was the day the fighting finally stopped, which is why it has become a major commemorative event across the globe.

The first Armistice Day

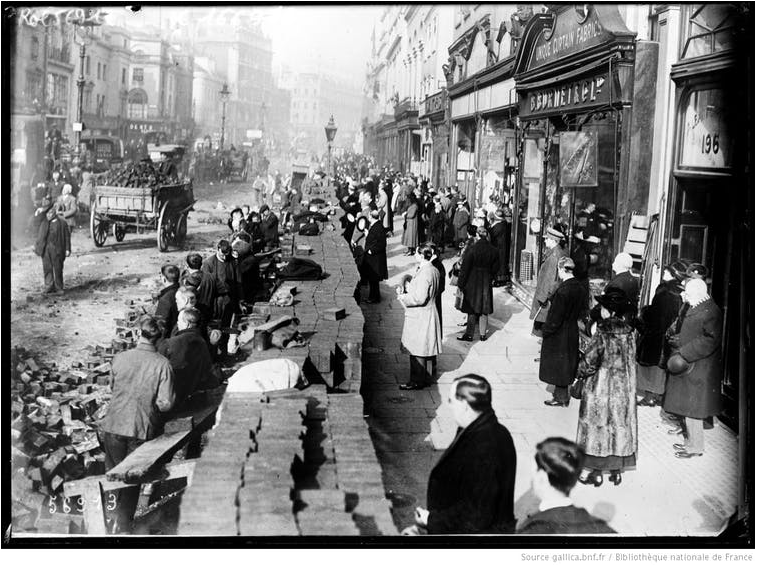

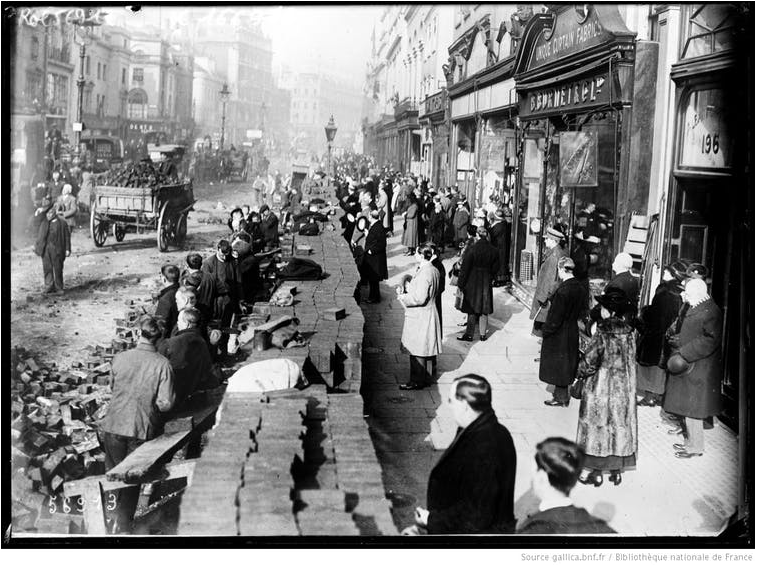

On the first Armistice Day, November 11 1918, crowds cheered on the streets of Allied countries such as Britain, Canada, Australia, New Zealand, the US, France and Belgium. People rejoiced at the ending of a period of total mobilisation that had affected every aspect of their lives, inflicting unprecedented hardship on soldiers and civilians alike.

But for those who had lost the war, the news of the armistice came as a shock. While some were relieved the conflict had ended, the sudden collapse of the German, Austro-Hungarian and Ottoman empires provided a breeding ground for revolutionary movements and further internal conflicts. For them, Armistice Day was a moment of anguish and bitterness.

The second Armistice Day (1919)

After its first iteration, Armistice Day became a more formal and sombre commemoration, and was often held at war memorials. People were encouraged to remember the dead with respect and solemnity.

A dedicated time for silence became part of the ceremony and has been central to Remembrance Day commemorations ever since. In Britain, King George V requested a two-minute silence, which was observed from 1919 onward across the Commonwealth. In France, the minute de silence was instituted in 1922.

Silence meant time for contemplation, reflection, introspection and, above all, respect. In multifaith empires where atheism was progressing, the gesture could conveniently replace a prayer.

Remembrance Day was deemed a civic duty for many, and the veterans would often take a lead role in its commemoration.

From then on, Armistice Day increasingly became known as Remembrance Day. The focus was no longer on the armistice and the end of the war: it became a day to remember, grieve and honour those who had died.

The notion of sacrifice became central to Remembrance Day, as those still alive tried to give meaning to, and cope with, the deaths of their loved ones. The language of memory honoured the deceased, acknowledging that they had not sacrificed themselves in vain but for institutions and values such as country, king, God, freedom and so on. However, as time passed, this language came to be increasingly contested.

Remembrance Day: the inter-wars and the second world war

Remembrance Day was also used to protest against war in general. Some mourners and veterans refused to attend official commemorations. In doing so, they showcased their anger at the state-sanctioned carnage that the first world war had been. In France and Belgium in the 1920s and 1930s, for instance, large pacifist movements used Remembrance Day and some war memorials to stress the futility of war and nationalism.

Such Remembrance Day protests were of openly political nature, and historical contexts altered the meaning of these demonstrations. Across Nazi-occupied Europe, clandestine Remembrance Day ceremonies were used as a sign of protest against German occupation during the second world war, and to remind them they had been defeated in the previous war.

Remembrance Day now

Today, the commemoration of the November 11 armistice is marked in many countries across the globe (mostly those on the “winning” side of the war) under various names: Armistice Day, Remembrance Day, Poppy Day, 11 Novembre, National Independence Day or Veterans Day. For some, the day is a public holiday.

Every state celebrating Remembrance Day grants different meanings to its commemoration. Speeches in France deplore the loss of lives and insist on the value of peace during official ceremonies. In Poland, however, the day marks the rebirth of the nation and a time to celebrate.

In the US, the commemoration is centred on the veterans of all wars, while in Australia few people attend Remembrance Day. The crowds prefer attending Anzac Day on April 25 – a more patriotic service and a public holiday.

As the first world war fades further away in time, one way to keep remembering those who died in this conflict has been to progressively include the commemoration of the dead of more recent conflicts in Remembrance Day ceremonies, as is the case in the US, the UK and France. The commemoration therefore remains relevant to a larger population but also prevents the multiplication of special days for official state commemorations.

Today, as in the past, protests continue to be a component of Remembrance Day. Recently, a man was fined £50 in the UK for burning a poppy on Remembrance Day to protest against current deployment of British forces. The commemoration has also been mobilised by different far-right movements across Europe to advance their agendas.

A centenary of remembrance

A hundred years after the event, Remembrance Day and first world war memorials still provide a time and place to remember those who fought and fell in the conflict. For the most senior citizens among us, this is their parents’ generation; a past they still live with.

On November 11 2018, to mark the 100th anniversary of the end of one of the world’s deadliest conflicts, you may choose to attend a Remembrance Day service. You may choose not to, or not even notice that it is Remembrance Day.

During the minute of silence, you may reflect on the meaning of war and its long-lasting impacts, its futility or its glory, think about a family member, or the weather. This degree of versatility partly explains the endurance of Remembrance Day. An official and public event, but also a personal gesture that everyone can embed with their own meaning.

This article can be found on The Conversation