Confirmation of 40 new genetic markers takes forward the development of the first tests to assess a person’s risk of developing glaucoma, a leading cause of blindness.

Australian researchers, including Flinders University Professor Jamie Craig, have published a pivotal paper in Nature Genetics after a genome-wide study of more than 134,000 people found 101 genetic markers that influence the fluid pressure in a person’s eye, called intraocular pressure.

High intraocular pressure is commonly associated with an increased risk of developing glaucoma.

Lead author Associate Professor Stuart MacGregor, director of the QIMR Berghofer Medical Research Institute’s Statistical Genetics laboratory, says the study shows 40 of the new genetic markers influencing eye pressure also increased a person’s risk of glaucoma.

He says the study found individuals with a large number of the genetic markers had an almost six-fold increased risk of developing glaucoma compared to someone who had fewer genetic variants.

“The discovery of these previously unknown genetic markers for glaucoma will be important for improving our ability to test for and predict a person’s risk of the disease,” Associate Professor MacGregor says.

“Although a predictive test for glaucoma is not available yet, our discovery is very promising.

If tests can identify who is most at risk of developing glaucoma at the earliest opportunity, those individuals can then receive the preventative treatment they need to stop them from going blind as they age.

“Early treatment is vital because once a person experiences vision loss, it is impossible to reverse.”

The report, entitled ‘Genome-wide association study of intraocular pressure uncovers new pathways to glaucoma’, was done in collaboration with multiple clinicians, hospitals and institutions across Australia and New Zealand, including the Menzies Institute for Medical Research and Flinders University.

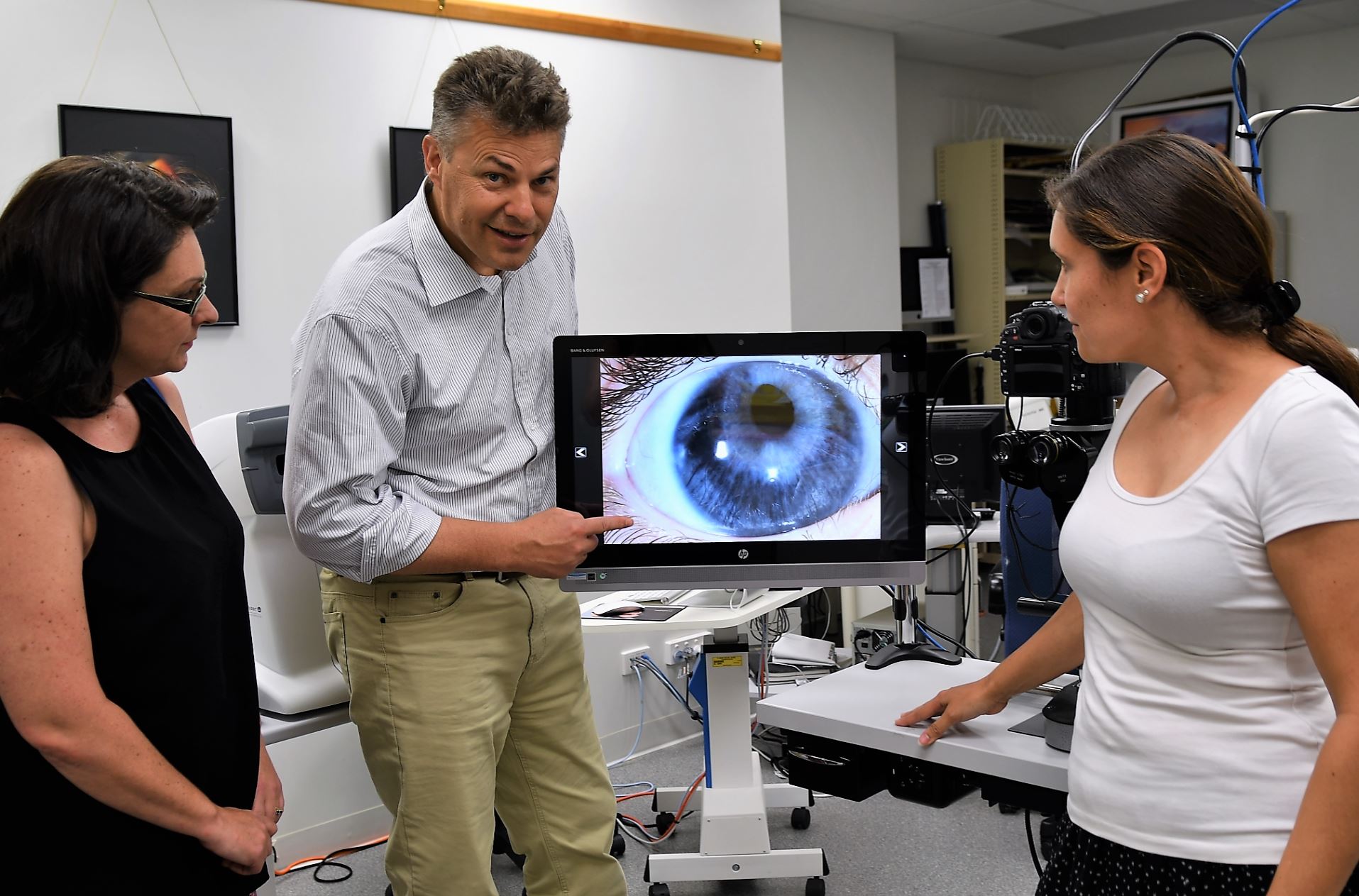

Matthew Flinders Distinguished Professor Craig, director of the Flinders Centre for Ophthalmology, Eye and Vision Research in the College of Medicine and Public Health, says the findings dramatically increased the current understanding of which genes cause glaucoma and high eye pressure.

“We expect far-reaching consequences in terms of predicting who will develop glaucoma in the population, and exciting possibilities to develop better ways to treat this disease, which is a leading cause of blindness worldwide,” he says.

“We have used DNA from thousands of patients with glaucoma to understand how these new genetic discoveries about eye pressure influence the risk of an individual developing severe vision loss from glaucoma.

“We are getting much better at predicting these outcomes in patients and this will help us find people at risk and get them on sight-saving treatment early in the course of the disease.”

A person’s risk of developing glaucoma – which damages the optic nerve and leads to a gradual loss of the peripheral vision – increased with age.

High eye pressure commonly associated with glaucoma can be treated with drugs, and even surgery.

The latest findings increase the number of known genetic markers underpinning intraocular pressure by more than 90.

The most surprising finding was the sheer number of those variants that were associated with developing glaucoma, researchers say.

“There is natural variation in eye pressure from person to person, and having high eye pressure doesn’t necessarily damage your vision,” adds Associate Professor MacGregor.

“So for the 101 genetic markers we identified, although they are a risk factor, their presence in your genetic coding doesn’t necessarily mean you will develop glaucoma.

“However, we were able to show 53 of the genetic markers do directly increase your risk of developing glaucoma and particularly increase the risk of developing advanced glaucoma, the type that tends to cause blindness.”

The genetic information of participants in the new study were from the UK Biobank and the International Glaucoma Genetic Consortium.

Glaucoma affects approximately 300,000 Australians and is the leading cause of irreversible blindness worldwide.

Although there is currently no cure, early detection through screening can halt or significantly slow the disease’s progression.

The research was supported by grants from the National Health and Medical Research Council and the Ophthalmic Research Institute of Australia, the BrightFocus Foundation.