Adelaide fossil hunters have taken a new look at when two early marsupials became extinct on the mainland of southern Australia.

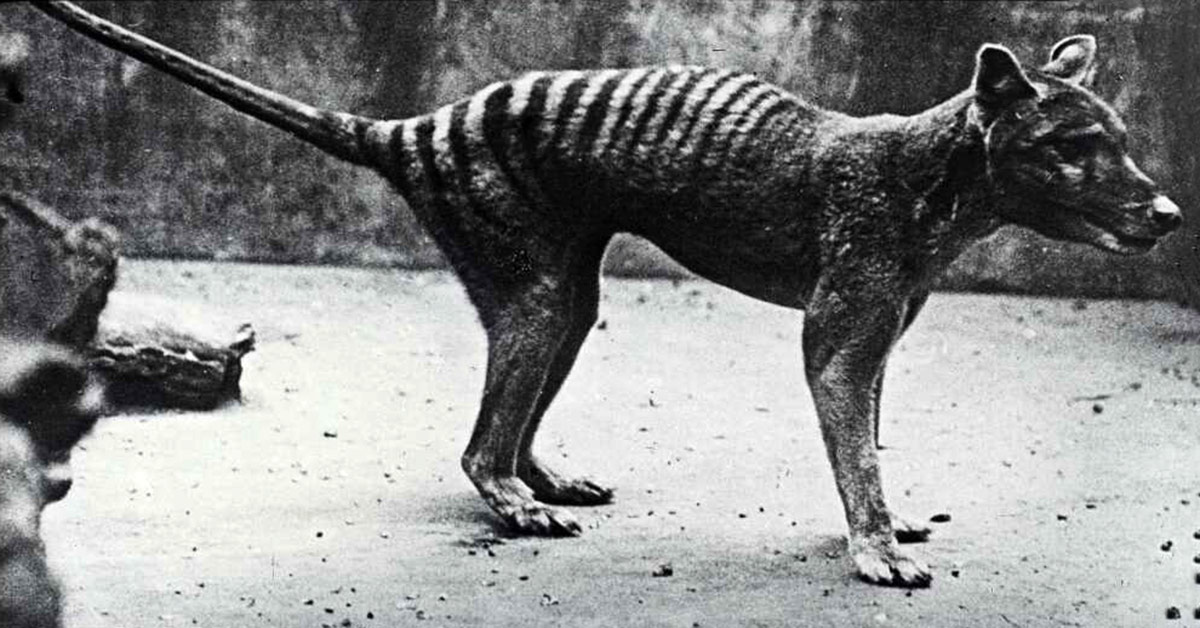

They have analysed new radiocarbon dates and found that thylacines (Tasmanian tigers) and Tasmanian devils went extinct on the Australian mainland at the same time, about 3,200 years ago.

For many years, scientists have been unsure exactly when thylacines and devils went extinct on the mainland.

A recent age for devil extinction (500 years before present) has recently been shown to be unreliable. The next youngest reliable devil fossil is 25,000 years old.

“Knowing when both species went extinct is important to understanding why they went extinct on the mainland, but survived in Tasmania,” says University of Adelaide co-lead author Dr Lauren White.

“Extinction at the same time would support the idea that a common factor (or set of factors) caused both species to go extinct.”

The team from the University of Adelaide and Flinders University used high-quality radiocarbon dates from thylacine and devil fossil bones from across southern Australia and statistical techniques to estimate the timing of extinction for both species on the mainland.

These new dates include the youngest fossil samples ever found for both species (3,245 years before present for the devil, and 3,290 years before present for the thylacine).

During the Late Pleistocene, the large marsupial carnivores Tasmanian devils (Sarcophilus harrisii) and thylacines (Tasmanian tiger or wolf, Thylacinus cynocephalus) were widespread over the Australian continent.

“A synchronous extinction of these species has almost always been assumed, but this is the first time that we have both a reliable dataset and robust statistical technique to validate this assumption,” says co-lead author, ecologist Dr Frédérik Saltré who is a palaeontology modeller at the new ARC Centre of Excellence for Australian Biodiversity and Heritage at Flinders University

“We estimated that both species went extinct on the mainland, at exactly the same time 3,200 years ago (plus or minus 50 years), which suggests that a common factor (or factors) were responsible for the mainland extinction.”

The researchers conclude that the fresh data will support further enquiries into the forces that drove these species to extinction.

The research by Dr White, with Associate Professor Jeremy Austin at the Australian Centre for Ancient DNA at Adelaide Univerisity, and Dr Saltré and Professor Corey Bradshaw both now at Flinders University, has been published in Biology Papers.