The entire knowledgebase on a giant megafaunal bird considered one of the most accurately dated extinct species in Australia has been smashed to pieces by South Australian researchers who say experts have been looking at the wrong egg the whole time.

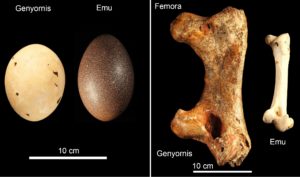

Dr Trevor Worthy, from Flinders University, and his team have found the first intact egg of the kind until now assumed to be from the giant Mihirung bird Genyornis – and they say it’s just one sixth of the size it would need to have been to gestate a Genyornis chick.

If Dr Worthy is correct, it’s a discovery that renders everything scientists thought they knew about the breeding and extinction of the giant mihirung Genyornis newtoni redundant.

Extensive dating of hundreds of samples of supposed Genyornis eggshell has led to the idea that it went extinct about 45-50,000 years ago, after living in Australia for millions of years.

Dr Worthy, an (ARC) DECRA Fellow at Flinders, worked with Dr Gerald Grellet-Tinner (visiting International Research Fellow in 2014 to Flinders) and Professor Nigel Spooner of Adelaide University, to turn all of that on its head.

In a paper published this week in Quaternary Science Reviews, Dr Worthy reports that the first complete egg is in fact 54,700 years old and the size of an emu egg, while Genyornis was, at an average of 275 kg, more than six times larger than an emu.

“I knew when I found this egg that it was something special, but did not realise then what potential it had to ruffle some feathers,” said Professor Spooner.

In another twist, Dr Worthy says his team has identified which species actually laid the egg.

To determine that, the investigators studied the egg’s microstructure, comparing it to various fowl and that of other mihirungs.

Their startling conclusion is that the egg and similar eggshell was probably laid by an extinct species of giant megapode in the genus Progura some 2-3 times larger than its living relative the malleefowl.

“I have studied fossil bird’s eggs all over the world, but here in South Australia, the challenge to find which bird laid the egg was made difficult because no chick bones have been found with these eggs,” said Dr Grellet-Tinner.

The twist in the story is that the giant megapode Progura has gone from being an obscure poorly understood extinct bird to one whose prehistoric distribution and extinction trajectory is one of the best known anywhere.

Dr Worthy says his main challenge now is to find the correct egg for Genyornis and begin re-establishing the knowledgebase destroyed by their discovery.

“Science, in testing ideas, often leads to unexpected outcomes. While our work has surprisingly shown that the basis for much of what we thought we knew about Genyornis is wrong, it does not alter the fact that a large and abundant bird went extinct about 45-50 thousand years ago, soon after humans set foot in Australia,” he said.