Scientists have discovered how one of the world’s biggest migration runs works.

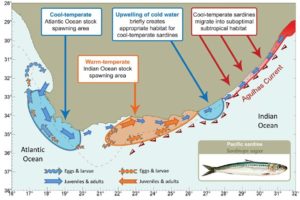

The Sardine Run involves the movement of hundreds of millions of sardines from their cool-temperate core range into the warmer subtropical waters of the Indian Ocean, on South Africa’s east coast.

The run is triggered by the upwelling of cold water on the southeast coast and as they swarm north, the sardine are sandwiched between the coast and a southward-flowing hot current that exceeds their physiological capacity. They are then targeted by huge numbers of dolphins, sharks, seabirds and even whales.

A new study in the journal Science Advances by South African and Australian scientists tested the hypothesis that the Sardine Run represents the spawning migration of a distinct east coast stock adapted to warm subtropical conditions. The scientists generated genomic data for hundreds of sardines from around South Africa, including data from regions of the genome that are primarily associated with differences in water temperature along the coast.

The results showed two sardine populations in South Africa, one in the cool-temperate west coast (Atlantic Ocean) and the other in warmer east coast waters (Indian Ocean). Each regional population appears adapted to the temperature range that it experiences in its native region.

“Surprisingly, we also discovered that sardines participating in the migration run are primarily of Atlantic origin and prefer colder water”, says Professor Luciano Beheregaray at the Flinders University Molecular Ecology Lab, one of the study authors.

“The cold water of the brief upwelling periods attracts the west coast sardines, which are not adapted to the warmer Indian Ocean habitat”, says author Professor Peter Teske from Johannesburg.

“This is a rare finding in nature, since there are no obvious fitness benefits for the migration, so why do they do it? “We think the sardine migration might be a relic of spawning behaviour dating back to the glacial period. What is now subtropical Indian Ocean habitat was then an important sardine nursery area with cold waters”, says Professor Teske.

This visually breath-taking migration run attracts tourists from around the world who are keen to get a glimpse of the underwater spectacle, but it may not be around forever.

“Given the colder water origins of sardines participating in the run, projected warming could lead to the end of the sardine run”, says Professor Beheregaray. Despite the huge numbers of fish involved, the run involves only a small portion of the South African population so while it’s end would mean the loss of one of nature’s most spectacular migrations, the effects on the population as a whole are likely to be negligible.