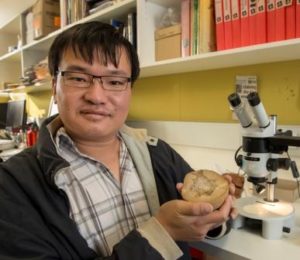

An ancient fossil fish that lived 423 million years ago – representing the earliest large vertebrate predator in the fossil record – has been described by an international team of researchers headed by Flinders University palaeontologist Dr Brian Choo.

Three specimens of the primitive fish Megamastax amblyodus – meaning “big mouth with blunt teeth” – have been unearthed from a site in Yunnan, China, and are now being housed at the Institute of Vertebrate Paleontology and Paleoanthropology at the Chinese Academy of Sciences, Beijing.

The largest specimen had a 17cm long jaw, with an estimated total body length of about one metre. It is believed to be an early sarcopterygian, the group that includes lung fish and limbed vertebrates, including humans.

The discovery has just been in Scientific Reports, a new UK-based research publication from the producers of the major international journal Nature.

Dr Choo, a Postdoctoral Research Fellow in the School of Biological Sciences, says his three-year investigation found that Megamastax existed during the Silurian period (443 to 416 million years ago) – refuting the long-held belief that large predatory fish did not emerge until much later in the Devonian period (410 to 360 million years ago).

“It’s always been thought that Silurian fish were all small because, until now, no fossils of species more than 30cm or so in length have ever been discovered,” Dr Choo says.

“But from the site in Yunnan, near the city of Qujing, we uncovered a diverse collection of jawed fish from Silurian sediments, including the new Megamastax, a predator vastly larger than any other vertebrate known from this age,” he says.

Dr Choo says the discovery “adds a new twist on our understanding of the ancient atmosphere”.

“As modern large fish tend to be more sensitive to oxygen availability than smaller ones, the apparent absence of big Silurian fishes has been used to calibrate some models of Earth’s atmospheric history, with supposedly lower oxygen levels restricting body size prior to the Devonian.

“However, evidence of a one metre-long fish swimming about 423 million years ago strongly refutes the idea.

“While by themselves, these fossils do not give an exact indication of what the atmosphere was like in the Silurian, they are still a significant new piece of the puzzle that will be incorporated into further research.”

Dr Choo says the breakthrough indicates that much of the earliest chapter of vertebrate evolution remains to be uncovered.

“These new fossils from Yunnan represent one of the earliest well-documented vertebrate faunas and demonstrate that fish from the latter part of the Silurian were already big and varied, clearly the result of an extended span of evolution.

“Unfortunately, the only fossils of jawed fish from much older sediments are a few tantalising fragments. There is a much deeper history about which we currently know very little.”